Article

Julia-Claudia. Results

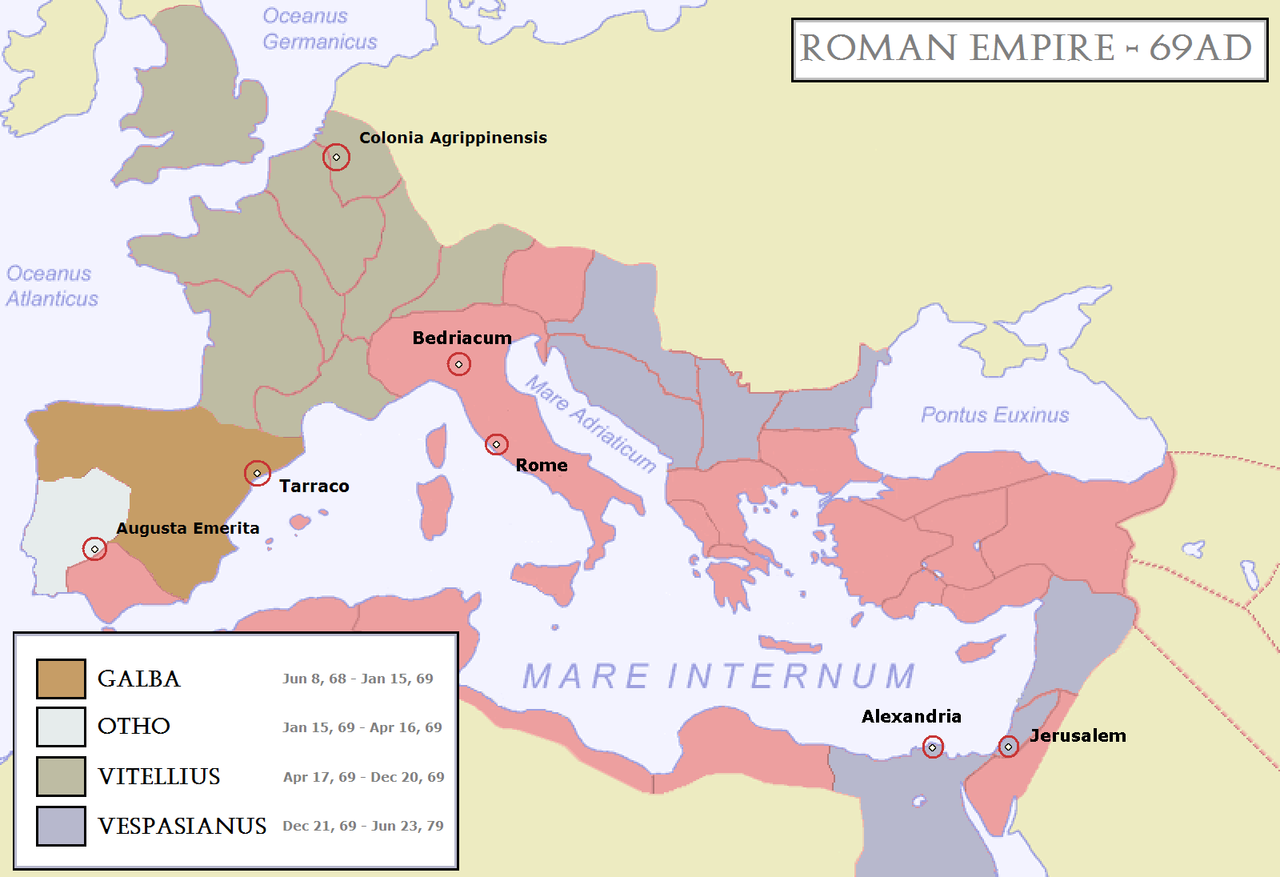

"The Year of the Four Emperors"

In 68 AD, Emperor Nero committed suicide, driven to despair by the widespread desertion of his supporters due to the approaching army of the rebellious commander Servius Sulpicius Galba. With Nero's death, the Julio-Claudian dynasty came to an end.

Galba failed to win the people's affection, as the plebeians, who had a warm regard for Nero, did not accept the one who overthrew their favorite in favor of the Senate. After Galba refused to pay the legions the promised reward, they rebelled against him.

The first to revolt were the Lower Germanic legions under the command of Aulus Vitellius. Then, in January 69 AD, in Rome itself, Nero's former friend Marcus Salvius Otho rose against Galba. The legionaries killed Galba and proclaimed Otho the new emperor.

However, Otho failed to reach an agreement with Vitellius. In April 69 AD, at the Battle of Bedriacum, the emperor was defeated by Vitellius and committed suicide.

Vitellius owed his power to the Lower Germanic legions, which caused discontent among the eastern and Danubian parts, historically rivals of the Rhine army. Their unwillingness to recognize Vitellius led to a new rebellion led by Titus Flavius Vespasian, who was at that moment suppressing a revolt in Judea. Handing over command to his son Titus, he marched on Rome.

In October 69 AD, the Second Battle of Bedriacum took place, in which Vitellius was defeated. He was ready to surrender on terms of personal safety guarantees, but his own army opposed the capitulation. Vitellius's supporters gave a final battle in Rome itself, resulting in the emperor's death and the complete defeat of his army. In December 69 AD, Vespasian became the new emperor, founding the Flavian dynasty.

Thus, the "Year of the Four Emperors" – the first civil war in the Empire – clearly demonstrated that the army had now become a key political force on which the fate of imperial power depended.

The Compromise Principate

By the second half of the 2nd century BC, after the final victory over Carthage, Rome had become the leading power in the Mediterranean region. If politics in the small Roman polis had previously been defined by the confrontation between titled patricians and untitled plebeians, now in the expanded state, the social conflict was between the nobiles and the populares.

The activities of the populares leaders, the Gracchi brothers, in the 130s and 120s BC led to the first exacerbation of the social crisis, which from the 80s BC turned into a whole series of civil wars: Sulla against Marius, Caesar against Pompey, and Caesar's heirs against his assassins. In the last civil war, Caesar's successors fought each other for the right to rule the Republic alone. The winner of this struggle was Octavian Augustus, who now needed to calm Roman society after 60 years of strife.

The compromise that satisfied everyone was the "Restored Republic." Augustus retained all the former republican magistracies headed by the aristocratic Senate; consuls, praetors, aediles, and quaestors were still elected, and real political competition between candidates resumed in elections. However, now at the top of the political system was a specific political figure – the "princeps," namely Augustus himself.

For the army, he was the emperor; for the magistrates, an official with numerous powers (consul, proconsul, tribune, censor, pontifex maximus); for the majority of the population, a man with enormous authority as a deliverer from civil wars and a "guarantor of stability." Control over the army, numerous administrative powers in the magistracies, and personal authority were the three key components of his power.

In historical science, different opinions have formed regarding the political regime created by Augustus.

The term "principate" was first used by Cornelius Tacitus in his "Annals." According to him, Augustus replaced the Senate, consuls, tribunes, and other magistrates. The historian concluded that "libertatem et consulatum" (freedom and consulship) of the Republic era were replaced by "principatus" (leadership) of Octavian. However, the "scourge of tyrants" refused to call the new regime a monarchy. For Tacitus, the princeps was something between a Hellenistic king and a consul, and the principate was between "true slavery and true freedom."

Theodor Mommsen viewed the issue differently. The German classic insisted on the diarchy of the Senate and emperors. In this system, the princeps was a key figure, yet limited by Roman law. The main elements of his power were proconsular imperium and tribunician powers. The princeps became an unaccountable absolute monarch only after Diocletian's reforms at the end of the 3rd century AD. It was Mommsen who divided Roman imperial history into the "Principate" (from Augustus to Diocletian) and the "Dominate" (from Diocletian onwards). Modern researchers consider the terms "Principate" and "Dominate" outdated and prefer to use "Early Empire" and "Late Empire."

Between the Senate and the People of Rome

The internal political dynamics of the time of the first Julio-Claudian dynasty were determined by the relationships of the emperors with the Senate, the equestrians, and the plebeians. Each Roman emperor built these relationships in his own way.

The creator of the Principate regime, Augustus, emerging victorious from the era of civil wars, managed to pacify all interested groups.

Tiberius, Augustus's stepson and the second Roman princeps, did not have the authority that his adoptive father had. He began his reign by strengthening the role of the Senate but gradually isolated himself on the island of Capri, sinking into melancholy and paranoia, entrusting governance to his favorites, such as Sejanus and Macro. Ultimately, the repressive processes of "offending majesty" undermined the Senate's influence, although the isolated Tiberius never openly opposed it.

If Tiberius became princeps at 56, Caligula did so at 25. He did not have the political experience that Tiberius gained before his reign, but he did have dynastic authority as the son of the plebeians' beloved Germanicus. Caligula's views were also influenced by his upbringing among eastern princes with their notions of the relationship between rulers and subjects. As a result, the third emperor openly opposed the Senate, relying on the equestrians and plebeians and bribing the latter with "bread and circuses." However, open confrontation against the more organized senatorial group ended disastrously for Caligula – four years after becoming princeps, he was killed along with his wife and child.

The conspirators hastily announced a return to republican freedoms but were met with resistance from the Praetorian Guard and the plebeians, who had already become accustomed to the princeps being their protector against the aristocracy. Thus, Claudius became emperor.

Instead of terrorizing senators like Tiberius and Caligula, he began creating a bureaucracy from his own freedmen – thus gradually forming a separate social layer that began to take over governance from the aristocracy. The absence of terror reconciled the emperor with the senators, and a generous policy of "bread and circuses" ensured the support of the plebeians. Claudius died either of natural causes due to old age or was poisoned as a result of female intrigues.

The next emperor, Nero, became princeps at 16 and, in some sense, repeated Caligula's path, as both admired Hellenistic culture. In the early years of his reign, Nero relied on representatives of the senatorial aristocracy – Seneca and Burrus – but then shifted to favorites among the plebeians, like Tigellinus, and began repressing aristocrats, portraying himself as a defender of the equestrians and plebeians. However, at some point, the emperor turned the western empire's military commanders against him, provoking a rebellion and being forced to commit suicide in the face of defeat.

In summary, Augustus, Tiberius, and Claudius did not openly oppose the Senate – Augustus relied on his personal authority, Tiberius isolated himself, maintaining his power through repressions and favorites, and Claudius, while generally agreeing with the Senate, created an alternative administrative structure in the form of a bureaucracy.

Augustus and Claudius also secured the support of the equestrians and plebeians through a generous policy of "bread and circuses." Only Tiberius, known for his stinginess, deviated from this, making him perhaps the most unpopular representative of the dynasty among the people.

In contrast, Caligula and Nero represented examples of open confrontation between imperial power and the Senate. Both young princeps sought to strengthen their sole authority, portraying themselves as defenders of the equestrians and plebeians against the senatorial aristocracy. However, for both, this open conflict ended in a series of conspiracies and eventual death.

Beyond Italy

The era of the first imperial dynasty of the Julio-Claudians marked the beginning of another long-term trend in Roman history – increased attention to Roman provinces beyond Italy.

Starting with Augustus, the empire was divided into senatorial and imperial provinces – this was part of the Principate era's compromise on the distribution of power. In senatorial provinces, governors were appointed from among former consuls, praetors, and quaestors. In imperial provinces, the princeps personally appointed their own legates, prefects, and procurators, mainly from the equestrian order. For example, the famous prefect of Judea during Tiberius's time, Pontius Pilate, was of equestrian origin.

Overall, under the Julio-Claudians, control over the activities of governors in both senatorial and imperial provinces was significantly strengthened, the rights of tax collectors were curtailed in favor of local communities and the imperial bureaucracy. Veteran colonies of Italians were established throughout the Mediterranean. Certain communities in Gaul and Spain were granted Roman citizenship, and under Claudius, part of the Romanized Gallic elite even entered the Senate. All these measures contributed to the integration of the provinces into the overall imperial space and set a trend for increasing the political role of provincials.

Augustus actively engaged in external conquests, expanding the empire to the banks of the Danube and the Elbe. However, under Tiberius, the empire's borders stabilized, and of the subsequent emperors, only Claudius dared to undertake a large-scale conquest expedition to Britain.

Nevertheless, the army was always at the center of the princeps' attention, as ultimately, their loyalty and professionalism ensured imperial power. The sad fate of Nero, who quarreled with military commanders, proved this.

New People

As a result of the "Year of the Four Emperors," the new ruler of Rome became Titus Flavius Vespasian, who became the first of three representatives of the Flavian imperial dynasty, ruling for the next 27 years.

In a certain sense, his personality can be called the "result" of all the aforementioned "trends" that occurred during the rule of the Julio-Claudians. Vespasian did not belong to the patrician order or the nobility but was a descendant of equestrians, who as the "middle class" rose precisely during the first imperial dynasty. For a long time, he was a military commander and came to power as a result of another military rebellion – this can also be considered evidence of the increasing role of the professional army in politics.

The Flavians themselves still belonged to the number of Roman families, but among the subsequent princeps of the Nervan-Antonine dynasty, representatives of the provincial nobility would already prevail. Thus, the political life of Rome gradually moved away from the customs of the Italian polis and acquired the features of an empire, laying the foundations of future Europe.

Take the test on this topic