Article

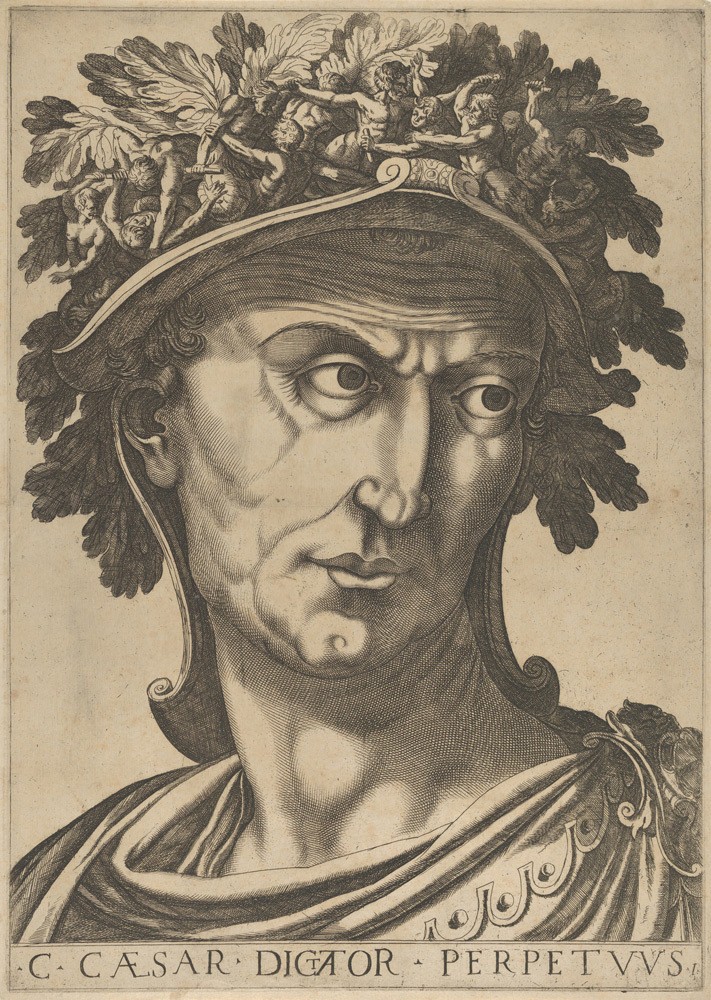

Divine Julius

The Beginning of Glorious Deeds

In the 2nd century BC, the Roman Republic reached the pinnacle of its power, establishing undisputed dominance over the entire Mediterranean. However, behind the external splendor of military victories lay deep internal contradictions: the dominance of the Roman nobility caused growing discontent among the plebeians. The people's tribunes, brothers Gaius and Tiberius Gracchus, attempted to carry out land reforms in favor of the poor but fell victim to the supporters of the aristocracy. These events split Roman society into the Optimates (for the "best") and the Populares (for the "people"), marking the beginning of a bloody era of civil wars.

In this turbulent era, in 100 BC, Gaius Julius Caesar was born—a descendant of the ancient patrician Julian family, whose lineage traced back to Venus herself. His ancestors held the highest state offices, from consuls to dictators, and even participated in drafting the sacred Laws of the Twelve Tables. However, despite their aristocratic status, the Julians supported the Populares. Caesar's aunt, Julia, was the wife of their legendary leader, the seven-time consul Gaius Marius, the sworn enemy of Sulla.

Young Caesar received an excellent education, largely thanks to his mother Aurelia, and mastered the Greek language, which for a Roman aristocrat of that time was a sign of true erudition. But it was not only his sharp mind that distinguished the future dictator—contemporaries noted his exceptional charisma and oratory talent. Even Marcus Tullius Cicero, the greatest orator of Rome, acknowledged: "His eloquence is brilliant and free from any intricacies; there is something majestic and noble in his voice, movements, and appearance."

The turbulent events of the era could not help but affect young Caesar. At eighteen, the patrician married Cornelia, the daughter of Marius's influential associate, the four-time consul Lucius Cornelius Cinna. When Sulla won the civil war, established a dictatorship, and began proscriptions—a terror against his political opponents—Caesar, as a relative of the enemies of the new regime, found himself in mortal danger. However, thanks to the intercession of influential patrons, the young aristocrat received a pardon. The acting dictator pardoned the future dictator but expressed his displeasure, prophetically noting: "There are many Mariuses in him [Caesar]."

Pardoned, Caesar left Rome and went to serve in Asia Minor. After Sulla's death in 78 BC, he returned and attempted to prosecute corrupt Sullans but lost. Nevertheless, the high-profile trials earned him fame as a defender of the people. To improve his oratory skills, he studied in Rhodes with Apollonius Molon, Cicero's mentor.

In 74 BC, Caesar participated in the defense of Asia against Mithridates Eupator, and later, thanks to connections, joined the college of pontiffs. Becoming a military tribune, he supported the restoration of the rights of the people's tribunes, limited by Sulla. Subsequently, Caesar actively collaborated with the people's tribunes, as he, being a patrician, could not hold this position.

In 69 BC, Caesar faced misfortune—his wife Cornelia and aunt Julia died almost simultaneously. But Caesar would not be himself if he did not make the most of this situation, and at the funerals, he publicly praised Marius and Cinna. For the first time since Sulla, an image of Marius was displayed in the forum, and this bold step strengthened Caesar's reputation as a defender of popular interests. Soon he was elected quaestor (treasurer), receiving a lifetime seat in the Senate along with the position.

In the same year, Rome faced a threat from Cilician pirates. Senate expeditions against them failed, and Caesar, along with Cicero, supported a law granting the outstanding commander Gnaeus Pompey extraordinary powers to fight the pirates and wage war against Mithridates. Thus, Caesar gained a new ally.

In 66 BC, Caesar was elected aedile (an official responsible for the city's infrastructure and public events), and by the following year, he found himself in enormous debt, having financed lavish games and the repair of the Appian Way. His main creditor became Marcus Licinius Crassus—a former associate of Sulla who amassed a fortune by buying up the property of the proscribed. Their alliance proved mutually beneficial: Caesar needed money, and Crassus needed an influential supporter among the Populares. In 63 BC, with Crassus's support, Caesar took the lifelong post of Pontifex Maximus, becoming the high priest of Rome.

In the same year, the conspiracy of Catiline—a bankrupt patrician who had twice failed in consular elections and decided to seize power by force following Sulla's example—was uncovered. The conspirators planned to assassinate consul Cicero and senators but were exposed by the great orator. Senate leaders demanded immediate execution, although Caesar opposed extrajudicial killings. Catiline fled and raised a rebellion but was defeated and died in battle.

After Catiline's defeat, Caesar became praetor and then went as governor to Spain. On the way, passing through a town in Narbonese Gaul, he remarked: "It is better to be first here than second in Rome." For the first time, Caesar tasted power, albeit provincial.

In Gades, seeing a statue of Alexander the Great, he exclaimed bitterly: "...at my age, Alexander already ruled so many nations, and I have not yet accomplished anything remarkable!" This ambition pushed him to active actions. Gathering 30 cohorts, Caesar suppressed the Lusitanian uprising, reached the Atlantic, and subdued the Callaici tribes, extending Roman territories to modern Galician lands. The army proclaimed him "imperator"—a victorious general.

Caesar also proved to be a skilled administrator: he reduced taxes, limited moneylenders, and prohibited creditors from taking more than two-thirds of a debtor's income. The trophies he obtained allowed him to pay off most of his debts. Now, having established himself as a talented military leader and administrator, he decided to become consul.

The First Triumvirate

At that moment, Pompey was celebrating his triumph in Rome after his brilliant success in the Eastern campaign. He not only defeated Mithridates, turning Pontus into a Roman protectorate, but also annexed Syria, establishing control over Judea. These conquests doubled the treasury's revenues, but the Senate, fearing the growing influence of the commander, blocked his demands for land grants for veterans.

Caesar, who also had the right to a triumph for the Spanish campaign, faced a dilemma: to celebrate victory or participate in the consul elections. According to the rules of the time, a candidate for consul had to be present in Rome in person, while a triumphator had to remain outside the Eternal City until the triumph itself. Caesar's absentee participation in the race was challenged by one of the Senate leaders, Marcus Porcius Cato, so the triumph had to be sacrificed for the elections.

To secure his victory, Caesar entered into an alliance known as the "First Triumvirate," where his ambitions combined with Pompey's military glory and Crassus's wealth. To strengthen the alliance, Caesar gave his only daughter Julia in marriage to Pompey. This "alliance of power, intellect, and money," as aptly put by French historian Étienne Robert, in 59 BC brought Caesar the coveted consulship, although the Senate imposed Marcus Bibulus, Cato's son-in-law, as his co-ruler.

Becoming consul, Caesar immediately showed his energy—he introduced the publication of Senate protocols, making meetings transparent, and proposed a land reform for Pompey's veterans with land purchase at market price at the expense of the treasury, replenished from eastern trophies. However, even this compromise project met fierce resistance from the Optimates led by Bibulus, Cato, and Cicero.

When Bibulus tried to block the reform, Caesar appealed directly to the people's assembly. As a result, his co-ruler was forcibly expelled from the forum, doused with manure, and his lictors were beaten. Humiliated, Bibulus effectively withdrew from affairs, giving rise to the joke about "the consulship of Julius and Caesar." Caesar then bypassed the Senate to pass all key decisions: he approved the land reform for Pompey's veterans and secured tax breaks for Crassus. The Triumvirate demonstrated its strength. Soon Cicero and Cato were exiled from Rome, and the great orator could only lament the "hopeless state of the Republic."

After his consulship ended, the Senate refused to grant Caesar a full proconsular province. However, he achieved his appointment as proconsul of Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum for an unprecedented term of five years through the people's assembly, and soon, thanks to Pompey's efforts, he also received Transalpine Gaul.

Nevertheless, despite his political successes, Caesar remained the junior member of the Triumvirate. Lacking Pompey's military glory and Crassus's wealth, he saw the path to greatness in conquests. Rich but fragmented Gaul became the ideal target. Thus began the famous Gallic War, where the future dictator's star truly rose.

The Gallic War

The opportunity for invasion quickly presented itself: the Germanic leader Ariovistus seized Alsace, and the Helvetii tribe began migrating through the lands of Roman allies. The Helvetii asked Caesar for permission to pass, but the proconsul deliberately delayed his response. The Gauls did not expect a swift strike—the proconsul gathered six legions, including two from the descendants of Marius's veterans, and defeated the Helvetii at Bibracte. He then turned against Ariovistus, defeating him at Vesontio.

The Gallic leaders recognized Roman suzerainty, but Caesar sought complete conquest. In 57 BC, he attacked the Belgae, defeating them on the river Axona. By 56 BC, the Veneti and Aquitani had fallen. Western Gaul was conquered.

In 55 BC, Caesar demonstrated Roman military might to the Germans by building a 400-meter bridge across the Rhine in 10 days. Two expeditions to Britain (55-54 BC) became the first Roman invasion of the island but were interrupted by the Eburones' uprising led by Ambiorix. After brutally suppressing the rebellion in 53 BC, a general Gallic uprising led by Vercingetorix broke out in 52 BC.

Despite a defeat at Gergovia in 52 BC, Caesar took revenge at Alesia, where Roman legions' engineering prowess and discipline decided the battle against superior Gallic forces. By 50 BC, resistance was broken. Gaul lay in ruins. Caesar gained fame as a great conqueror, became incredibly wealthy from trophies and plundering the province, but most importantly, he gained 10 battle-hardened legions personally loyal to their commander. This made him the strongest member of the Triumvirate.

While Caesar was conquering Gaul, his political opponents were not idle. In 57 BC, Cicero and the implacable Cato returned from exile and immediately engaged in the struggle against Caesar's growing influence. Cato insisted on prosecuting Caesar for exceeding his powers in Gaul and demanded he be stripped of his proconsular authority.

With each victory, the commander's popularity and influence grew. Fearing Caesar's ambitions, the senatorial oligarchy did everything possible to weaken his position. However, in 56 BC, Caesar seized the initiative, organizing a meeting of the Triumvirs in Luca. It was decided that Pompey and Crassus would become consuls for 55 BC, and their proconsular provinces of Spain and Syria would be secured for them for a five-year term.

Although the Triumvirs fulfilled their obligations to Caesar, each pursued their own goals. Pompey needed the consulship to strengthen his position in the Eternal City. Crassus, feeling he lagged behind his allies in glory and authority, sought to match them with military successes. He chose Parthia, but this campaign ended in disaster. In 53 BC, the Roman army was decisively defeated at Carrhae, and Crassus perished.

Thus, the Triumvirate, once dictating Roman policy, was reduced to a tandem of Caesar and Pompey. By then, Pompey began to see the rapidly strengthening Caesar as a threat and started aligning with the Optimates, who in turn recognized him as their new leader, lacking the reputation of a radical reformer. In 54 BC, Julia—Caesar's daughter and Pompey's wife—died, severing the last tie binding the former allies. When Caesar offered Pompey to marry his grandniece Octavia, he refused.

Civil War

Although Caesar still had many supporters in Rome, the Optimates felt their advantage. Cato did not cease his attempts to bring Caesar to trial and strip him of power, but the proconsul's supporters blocked these initiatives. Caesar understood well that without an army, he faced inevitable trial and exile. He tried to negotiate, made concessions, and even proposed a compromise—he and Pompey would disband their legions and relinquish their proconsular powers together. This proposal received widespread approval in the Senate, even supported by Cicero, but Cato and Pompey remained adamant.

The leaders of the Optimates deliberately provoked Caesar to extreme measures, knowing that in ordinary legal political struggle, he would defeat them due to his popularity and wealth. Cicero, who tried to mediate, could no longer prevent the inevitable.

In 50 BC, Caesar's loyal tribunes, Mark Antony and Quintus Cassius Longinus, vetoed a law declaring him an enemy of the Republic. In response, the Senate passed the "senatusconsultum ultimum"—an emergency decree overriding the tribunes' veto. Pompey's troops began gathering in Rome, and the tribunes had to flee to Gaul.

Gathering the XIII Legion, Caesar told his soldiers that the Senate had violated the sacred rights of the tribunes and his own dignity. In January 49 BC, upon learning he had been declared an outlaw, he approached the Rubicon. According to legend, crossing the river, Caesar declared: "The die is cast." The civil war began.

Caesar's troops swiftly occupied city after city. Pompey did not expect such speed and was caught off guard. He did not have a formidable army in Italy and hastily fled with the leaders of the Optimates to Greece. Caesar occupied Rome without a fight, but unlike Sulla, he declared an amnesty instead of terror.

In 48 BC, Caesar crossed into Greece and dealt a crushing defeat to Pompey on the plains of Pharsalus. The defeated commander fled to Egypt, hoping to find refuge with King Ptolemy XIII. But Egyptian courtiers, eager to ingratiate themselves with the victor, treacherously stabbed the fugitive, presenting his head as a gift to Caesar. However, instead of gratitude, Caesar was enraged, for he intended to magnanimously pardon Pompey. Caesar deposed Ptolemy XIII, who died in street battles, and placed the deceased king's sister and his lover, Cleopatra, at the head of Egypt.

In 46 BC, at the Battle of Thapsus in Africa, Caesar defeated a new army of the Optimates. Upon hearing of the defeat, Cato committed suicide. In 45 BC, Pompey's elder son Gnaeus gathered a new army in Spain but was also defeated at Munda. Caesar finally triumphed in the civil war, after which he pardoned the surviving Optimates, including Cicero, Marcus Junius Brutus, and Gaius Cassius Longinus.

Dictatorship

Caesar understood well that military force alone was insufficient to legitimize power. Unlike Sulla, who immediately established a perpetual dictatorship, Caesar acted gradually. In the summer of 49 BC, he first received dictatorial powers—for only 11 days—"to hold elections." In 48 BC, the leader of the Populares became a dictator for a year "to conduct the war." In 46 BC, his dictatorship was set for 10 years, and at the beginning of 44 BC, it became lifelong.

But Caesar did not limit himself to dictatorship alone. He combined it with the consulship, the lifelong position of Pontifex Maximus, censorial powers, and the rights of a people's tribune. The conqueror of Gaul's power became all-encompassing de jure and de facto, and even Sulla in his time did not possess such. The once all-powerful Senate now merely formally approved the decisions of the "Father of the Fatherland." The cult of Caesar's personality reached incredible proportions—his profile was minted on coins, and cults were established in his honor. Cicero wrote bitterly about the "night of the Republic."

Contemporaries accused Caesar of striving for royal power, but he was in no hurry to restore the monarchy. Unlike Sulla, he genuinely enjoyed great popular love and could openly disregard republican legality but not abolish the Republic—its traditional magistracies continued to function, though they lost their former significance.

Caesar remained faithful to the Populares program. He relied on the army, the equestrians, and the plebs, continuing to distribute bread, organize public feasts, and create jobs. Veterans received land in Italy and the provinces, and the provincial elite was actively involved in governance. As Theodor Mommsen noted, Caesar created a "democratic monarchy"—a regime where the traditional aristocracy lost power, but broad layers gained significant benefits. Sulla, with his dictatorship and terror, sought to restore the dominance of the senatorial aristocracy. Caesar, with his dictatorship and mercy, wanted to completely abolish this power, restructuring the republican mechanism for himself. If the broad masses tolerated Sulla's power, they genuinely rejoiced at Caesar's power.

Caesar planned even greater transformations and intended to start a grand war with Parthia. But these plans were not destined to come true. The nobility harbored fear and hatred for the reformist dictator. A conspiracy against him matured, led by the once-pardoned Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. It seemed Caesar deliberately ignored numerous warnings of the impending assassination. On March 15, the fateful "Ides of March," the dictator, at the height of his power, was stabbed in the Curia of Pompey.

However, the assassins did not offer a clear political alternative and were soon forced to flee Rome—the murder of the beloved dictator provoked the fury of the broad masses. Caesar's heir became his grandnephew Octavian, who was destined to deify Caesar, avenge Brutus and Cassius for the death of his adoptive father, and, after winning several civil wars, transform the Roman Republic into an Empire.

The Optimate Sulla discredited the dictatorship in the eyes of the "lower classes," while the Popularis Caesar discredited it for the "upper classes." Now, for all Romans, it was associated with tyranny. Therefore, Octavian would reject the idea of an open dictatorship. His sole power would be secured by traditional republican magistracies and control over the provinces. He would create the illusion of "restoring the Republic" for the Romans, calling himself the "first citizen," as the Romans could not tolerate an open king or tyrant over themselves. Thus, although Caesar was not the founder of the Empire, he became the direct predecessor of its real creator—Octavian Augustus.

Take the test on this topic