Article

Happy dictator

The Youth of a Future Dictator

One of the most controversial figures of the late Republic, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, was born in 138 BC and came from an ancient but impoverished patrician family. As early as the 4th–3rd centuries BC, his ancestors had become consuls and dictators, but in 275 BC, Publius Cornelius Rufinus was expelled from the Senate for having "more than ten pounds of silverware"—an unforgivable luxury by the standards of the early Republic. This is how Plutarch explains the decline of the family, after which Sulla's ancestors did not rise above the rank of praetor.

The future dictator, it seems, received an excellent education, was fluent in Greek, and was very successful with women. However, the poverty (by noble standards) of his father forced the young man to live in an insula (apartment building) rather than in his own mansion.

By that time, Rome had already become the strongest power in the Mediterranean, where, as a result of numerous conquests, a stream of trophies, slaves, jewels, and tribute flowed. The main beneficiaries of the successes were the nobility, who received huge profits from vast land holdings and distributed key political positions within their class. Meanwhile, veterans of numerous wars could not compete with large estates and, having gone bankrupt, sold their plots to the same nobles. The impoverishment of the class of small landowners, who had to buy their own equipment, undermined the mobilization base of the army.

Additionally, a conflict was brewing with the Italics—ally tribes in Italy without Roman citizenship, whose land was actively seized, although they made up a significant part of the army. For every Roman legionnaire, there were about 1.5 to 2 Italic soldiers.

In the 130s and 120s BC, the brothers Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus led a popular movement to redistribute land, but were ultimately killed.

Sulla himself at that time was unlikely to think of a serious political career due to the relative modesty of his position. He preferred a riotous lifestyle in the company of jesters and mimes—people who, by Roman standards of the time, were at the bottom of the social hierarchy. At some point, Sulla became involved with an elderly but wealthy freedwoman, Nicopolis, who bequeathed her fortune to him. Thanks to this inheritance, in 107 BC, he was able to be elected quaestor, that is, treasurer.

By that time, Sulla was already 30 years old. Having known need and "hardened" by life, he had become skilled in the art of acting and was now determined to fight for his "place in the sun." As quaestor, Sulla went to Africa to war against the Numidian king Jugurtha.

In the Shadow of Marius

Numidia was located in the territories of modern Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya and was an unpleasant place—the arid climate in the mountains and deserts was a serious test for the legionnaires. After the Romans' victory over Hannibal, this country effectively became a protectorate of Rome, but at some point, King Jugurtha overthrew another king, Adherbal. Since the latter was an ally of Rome, in 111 BC, the Senate declared war on the new ruler.

Jugurtha had experience serving in Spain under the destroyer of Carthage, Scipio Aemilianus Africanus, and proved himself a talented commander who had become acquainted with the structure of the legions. The king understood the impossibility of defeating the Romans in a direct confrontation and instead decided to take advantage of the terrain, imposing a guerrilla war.

To the displeasure of the plebs, none of the Roman commanders could achieve decisive success. After several changes of commanders, in the consular elections of 107 BC, the victory was won by the low-born Gaius Marius—another student of Scipio. He unified the system of training and equipping legionnaires, and most importantly, abolished the property qualification, promising soldiers land for service.

The successes of the "new type of army" after thorough military training were not long in coming. Marius quickly took the most important cities for Jugurtha—Capsa, Thala, the Muluccha Citadel, and Palla. Along with these cities, the Numidian king lost a significant part of his treasury.

On Marius's orders, Sulla recruited cavalry in Italy and arrived in Numidia. According to Sallust, he quickly mastered all the intricacies of military affairs, quickly adapted to the army environment, and gained popularity among the legionnaires.

However, Jugurtha did not waste time, recapturing Cirta—the capital of the Numidian kingdom—from the Romans. Marius, along with Sulla, moved to reclaim the city. Near Cirta, a general battle took place against the combined forces of the Numidians and Mauritanians. Sulla, at the head of the cavalry, successfully flanked the enemy and, together with the rest of the consul's army, completed the rout.

Marius understood perfectly well that pursuing Jugurtha through the mountains and deserts of Numidia could continue indefinitely, so he resorted to cunning. The commander sent a diplomatic mission to the Mauritanian king Bocchus, led by Sulla and legate Aulus Manlius—it seems the consul already highly valued the talents of the cavalry commander. Bocchus agreed to hand over Jugurtha in exchange for territories in Western Numidia. Then Marius entrusted Sulla with conducting a whole special operation to capture the Numidian king. Under the pretext of meeting with a Roman envoy, the Mauritanians lured Jugurtha, captured him, and handed him over to Sulla. The war was over.

In 105 BC, Marius finally suppressed the resistance of the Numidians and placed a king loyal to Rome on the throne. In the same year, the commander returned to Rome and celebrated a grand triumph. The captive Jugurtha was paraded in the triumph and then starved to death after the celebration. The glory of the victor also went to Sulla, who successfully commanded the cavalry and personally captured the king. Later, already an old man, Sulla would insist that he had always been Fortune's favorite, "fortunate for himself and the Republic"—was it then that he believed in his "star"?

While Marius and Sulla were fighting in Africa, a Germanic invasion occurred in the north. In 105 BC, the tribes of the Cimbri and Teutons invaded the province of Narbonese Gaul. At Arausio, the Roman army was defeated with catastrophic losses—Titus Livius cites a figure of 80,000 soldiers and 40,000 camp followers with servants. Although these are clearly fantastic and exaggerated numbers, the historian provided them to emphasize the complete rout. Panic erupted in Rome, as the path to Italy was open to the enemy. However, the leaders of the Germans and Celts preferred to invade Spain. The capital of the Republic was given a respite.

Marius, who had not yet returned from Africa, was elected consul in absentia, which was already an exceptional measure, as a candidate for consul was usually required to be present in person at the elections. Upon arriving in Italy, Marius immediately began reorganizing the remnants of the Roman army, scaling his previous reforms to all Roman legions. He preferred to leave his veterans in Africa, as the soldiers were exhausted after a long war and needed a break. Only his "officers," including Sulla, went to war with the consul.

Already in 102 BC, Marius defeated the Teutons at Aquae Sextiae, and in 101 BC, the Cimbri were defeated at Vercellae. Marius became not only the hero of the Jugurthine War but also the savior of the Fatherland. Sulla, during the war, captured the leader of the Tectosages tribe, Copillus. Later, he managed to prevent the Marsi tribe from siding with the Germans and persuaded them to ally with Rome.

During all the wars, Marius continuously held the office of consul for 5 years—a remarkable honor since the early Republic and quite symptomatic. Sulla was still serving as Marius's legate, but soon he would step out of his commander's shadow.

The Rise of Sulla

The 90s BC were surprisingly calm for Rome. So calm that sources barely cover this decade. We know that Sulla, thanks to his military successes and friendship with the Mauritanian king Bocchus, was able to be elected to the position of urban praetor—the ancient Roman equivalent of a judge in civil cases.

After his praetorship, Sulla was appointed proconsul in Cilicia in southeastern Asia Minor. Here, as a governor, he had to intervene in a civil war in Cappadocia on the side of the pro-Roman king Ariobarzanes against the usurper Gordius, who was supported by the Pontic king Mithridates VI Eupator. At the head of a small detachment, Sulla managed to defeat Gordius's forces. At the same time, an embassy from Parthia arrived to the governor, making Sulla the first Roman official to establish diplomatic contact with the powerful eastern neighbor of the Republic.

Returning to Rome, Sulla found it in a state of another crisis. This time, passions were boiling around the Italics—tribune of the people Marcus Livius Drusus was promoting a bill to grant the Italics the rights of Roman citizenship, as the Republic's army was largely replenished at their expense.

Suddenly, Drusus died. His death aroused suspicion among the leaders of the Italics, who believed that Drusus's "murder" put an end to the possibility of negotiating with the Senate. The Italic communities of southern and central Italy rose in rebellion. The Social War (91–88 BC) began.

Sulla and the elderly Marius participated in it as legates. The troops under Sulla's command defeated the Italics in Samnium and Campania and took the capital of the rebels, Bovianum. Nevertheless, the Senate made concessions—citizenship was granted to the communities in the north that remained loyal to Rome. Subsequently, it spread to the rebellious regions, although the votes of the "new" citizens were not equal to those of the "old" ones. As a result of the pacification of the Italics, Sulla became a hero of the Republic and in 88 BC intended to achieve the position of consul.

Meanwhile, the previously mentioned Pontic king Mithridates invaded Roman Asia, causing a massacre—according to Appian, 150,000 people were killed. Against this backdrop, Sulla was successfully elected consul and led an army to a new war. However, after his departure, Marius, who wanted to regain his fame as the chief commander, organized a conspiracy. Together with the tribune of the people Publius Sulpicius, they managed to push through a law transferring command to Marius.

Then Sulla made a counter-move. His army included many veterans of the Social War. Now, thanks to Marius's reforms, the legionnaires were more loyal to their own commanders than to the "Senate and people of Rome," as it was the commander who promised them trophies and land allotments. The change of commander threatened Sulla's veterans with being bypassed by Marius's veterans. With the support of the army, the consul refused to obey the law and turned the army on Rome, which he took by storm for the first time in the history of the Eternal City.

Marius fled to Africa, and Sulpicius was betrayed by his own slave. The slave was freed for his assistance and immediately executed for treason as a free man.

War and Dictatorship

In 87 BC, as proconsul, Sulla went to war against Mithridates, after which his unfinished enemies raised their heads again. Marius returned to Rome and was even elected consul along with his supporter Lucius Cornelius Cinna. They organized a series of show executions, but soon the 70-year-old Marius died. Cinna, having lost his ally, was forced to seek new support and found it in the Italics—he equalized their votes with the Romans.

Meanwhile, in the East, Mithridates captured vast territories in the Roman province of Asia in western modern Turkey and invaded Greece. First, Sulla took Athens, then defeated the Pontics at Chaeronea in 86 BC and Orchomenus in 85 BC. For the victories won, the army proclaimed Sulla "imperator." At that time, this title meant a victorious commander, not a ruler of the state. Mithridates was forced to leave the Balkans and agreed to peace. Due to the civil war in Italy, Sulla did not finish off the external enemy: Mithridates simply renounced his conquests and paid a contribution that allowed Sulla to maintain his army.

Cinna sent legions to Greece to capture Sulla, but they preferred to side with the proconsul. In 84 BC, during an attempt to gather a new army, Cinna was killed. After his death, the Marian faction was led by the son of the deceased commander, Gaius Marius the Younger, who could not organize worthy resistance. In 83 BC, Sulla landed in Brundisium in southern Italy and took Rome for the second time.

In 82 BC, he appointed himself dictator "for the writing of laws and the strengthening of the Republic." Dictators had not been appointed since the Second Punic War. Moreover, instead of the usual 6 months, Sulla's dictatorship was declared indefinite. Cicero would later say that "the nobility regained power in the Republic with fire and sword."

Now on the Roman Forum, tablets with the names of those declared outlaws—proscriptions—were posted. A reward was promised for each killed, and slaves were promised freedom. The property of the proscribed was subject to confiscation. In this simple way, the dictator spared himself the need to conduct search operations, as money-hungry citizens themselves brought in everyone needed.

The process immediately got out of control, and not only Sulla's enemies but also many wealthy citizens not connected with Marius's party fell under the terror. However, many of the dictator's friends enriched themselves by buying up the confiscated property of the repressed. The most famous of them was Marcus Licinius Crassus—the future victor over Spartacus. But the future political ally of Crassus—Gaius Julius Caesar, whose family was connected with Marius—miraculously escaped death thanks to the intercession of friends. Sulla yielded to persuasion and did not execute Caesar, but nevertheless saw a potential threat in the young man, saying that "there are many Mariuses in him." And he was not mistaken: a few decades later, Caesar himself would become a perpetual dictator.

Having rid himself of the opposition, Sulla set about reforms. He clarified the cursus honorum—the order of holding offices, so that now, to avoid the usurpation of power, no magistrate could be re-elected to office within 10 years after the previous term. The dictator doubled the number of senators—from 300 to 600, the number of praetors—from 6 to 8, and the number of quaestors—from 8 to 20. The courts were transferred to the Senate, and Sulla's veterans were universally granted land plots in Italy at the expense of the Italics. At the same time, to avoid new unrest from the latter, the dictator retained Cinna's law on the equality of votes with the Romans.

Most importantly, Sulla deprived the tribunes of the people of most of their rights. Now they could not convene the Senate, were deprived of the right of legislative initiative, and could not be elected to any other position while holding this office. The dictator intended to nip in the bud the possibility of new "Gracchi" appearing.

Sulla realized that his transformations were primarily upheld by the power of the legions, not the laws. To ensure that no one in the future could repeat his own success, the dictator forbade commanders from appearing in Italy with an army—a commander was obliged to disband it before returning to Rome. The northern border of Italy was designated as the Rubicon River.

The dictator did everything to strengthen the senatorial aristocracy and weaken the grassroots movement of the populares, trying to roll back the Republic to times of undisputed dominance of the nobility, when the Sulla family itself "shone." Paradoxically, the usurper used tyrannical methods to try to return to times when such usurpation was impossible, and dictators laid down their powers months, or even days, after appointment, rather than holding this position indefinitely. It is thanks to Sulla that the word "dictator" acquired the familiar association with usurpation and tyranny, rather than with the heroic "salvation of the Fatherland," as it was before.

Having considered his work done, in 79 BC, Sulla suddenly resigned and declared that he was ready to be held accountable for all his actions. No accusers were found. The nobles highly appreciated the dictator's efforts, and even Cicero, who later branded Caesar a tyrant and usurper, called Sulla's reforms a "morally beautiful deed." Did contemporaries realize that Sulla created a dangerous precedent that would allow another eminent commander to cross the Rubicon and take Rome again in just 30 years? Or did they sincerely believe that the "Republic was strengthened" and the "cause of the nobles" had triumphed? Ironically, Cicero himself would also be killed, ending up in the proscriptions of Mark Antony.

It should not be thought that Sulla was the cause of the fall of the Republic. Rather, he was a vivid symptom, like Marius, who held the office of consul an anomalous seven times. Researchers see in Sulla's dictatorship a prologue to the activities of Gaius Julius Caesar and Octavian Augustus. Some even call him the first Roman monarch.

The man who first in the history of the Eternal City took it by storm and seized power by force, voluntarily renounced it. Sulla spent the rest of his days on a villa, hosting lavish feasts as in his youth, and in his free time, he read literature obtained in Greece. He died in 78 BC from an unknown illness, having lived a life certainly "fortunate for himself," but "fortunate for the Republic"?

Take the test on this topic

History

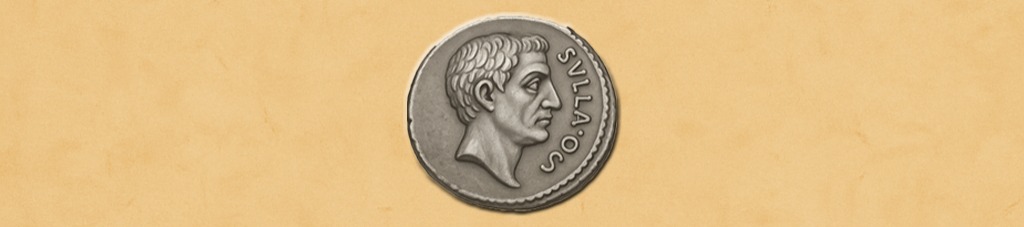

Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Impressed by the story of the first Roman dictator of the "new type"? Now take the test and check your knowledge!