Article

Tiberius: Emperor Against His Will

Stepson of the Princeps

The future emperor was born in 42 BC at the height of the civil war between the allies of the slain Caesar and the republicans. He came from the ancient patrician Claudian family, and his father, Tiberius Claudius Nero, was an experienced military leader who first served under Caesar and then Mark Antony.

The Claudians found themselves in the whirlwind of political storms. Initially siding with Mark Antony, they fled Rome after the defeat in the Perusine War against Octavian. However, in 39 BC, shortly after the amnesty, Octavian fell in love with Tiberius's mother, Livia, secured her divorce, and married her, even though Livia was already pregnant with Drusus. Thus, Tiberius became the stepson of the most powerful man in Rome.

Nevertheless, Tiberius and his younger brother Drusus were raised in their biological father's house, receiving an excellent education in the Greek spirit along with thorough military training. Both boys were remarkably talented and healthy, although they differed greatly in character: the reserved and restrained Tiberius was the complete opposite of the sociable and good-natured Drusus. Despite their differences, the brothers maintained a warm relationship throughout their lives.

After their father's death in 33 BC, the nine-year-old Tiberius delivered his first public speech at the funeral, demonstrating abilities beyond his years. The perceptive Octavian immediately recognized the potential of both stepsons. During his triumph in 29 BC, following the final victory over Mark Antony, the emperor took them as his companions.

Military Leader and Administrator

Tiberius began his military career at the age of 15. In 26 BC, he became a military tribune in Cantabria, where under the command of Agrippa, Augustus's best general, he participated in the war against local tribes. This campaign served as an excellent school of military art for him.

Three years later, in 23 BC, Tiberius brilliantly resolved a crisis in Rome's grain supply, demonstrating extraordinary administrative abilities. Velleius Paterculus aptly noted: "By his actions, he revealed what he would become," predicting Tiberius's future successes.

Augustus began entrusting his stepson with increasingly responsible tasks. Tiberius participated in important legal proceedings and investigated abuses in Italy. In 23 BC, he acted as a prosecutor against the conspirator Fannius Caepio, when he first applied the law on insulting the majesty of the Roman people — a tool that would later play a sinister role.

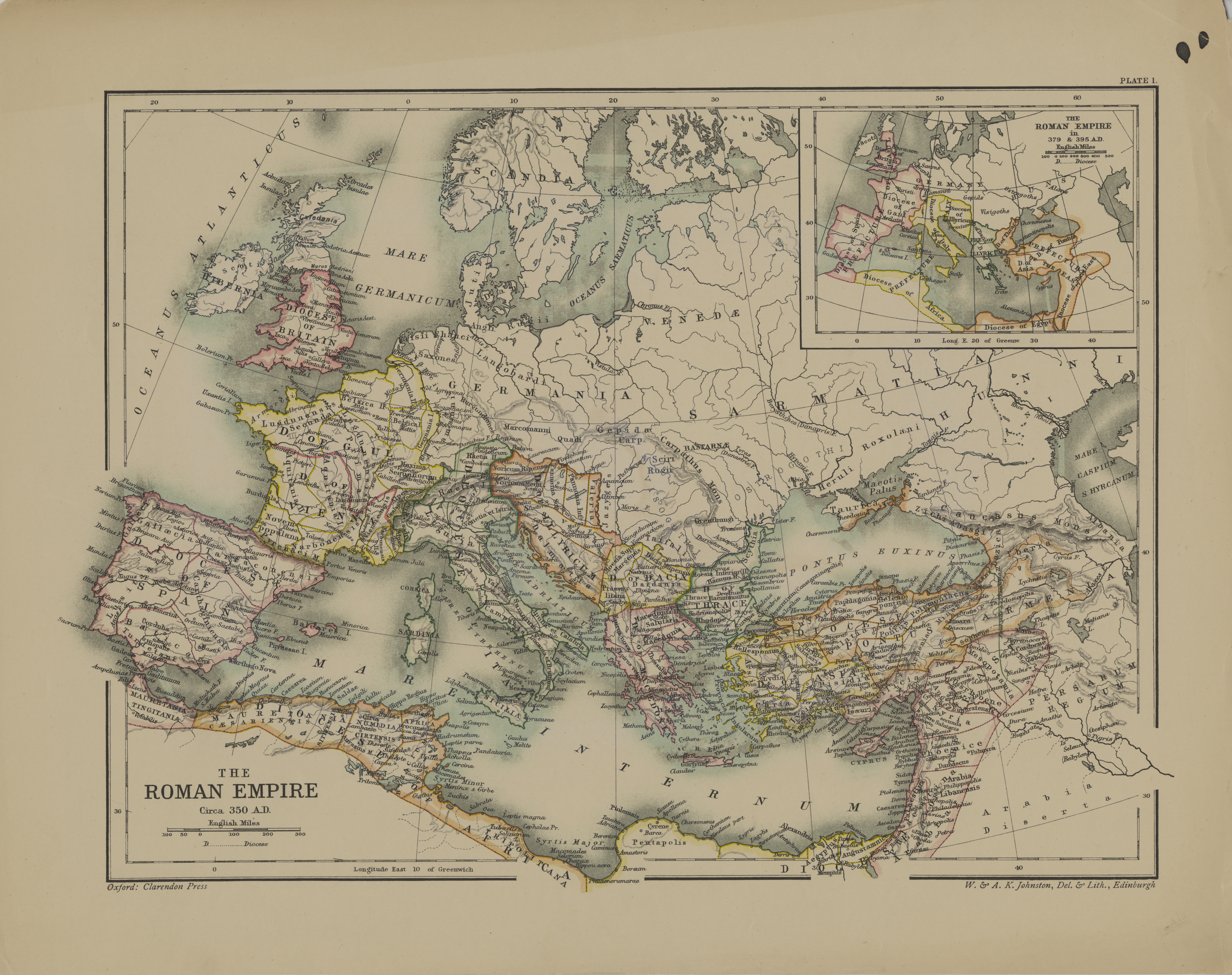

In 20 BC, Tiberius led a crucial diplomatic mission to Parthia, where he brilliantly resolved the Armenian question. He managed to place the loyal Tigranes III on the Armenian throne and secured the return of Roman standards lost at Carrhae in 53 BC. This diplomatic triumph significantly strengthened Rome's position in the East.

As a reward for his successes, Augustus appointed Tiberius as the governor of Transalpine Gaul in 19 BC. The young governor proved to be a capable administrator, successfully dealing with regular rebellions and barbarian raids.

In 16-15 BC, Tiberius, as a praetor, led a campaign against the Alpine tribes of the Raeti and Vindelici. He was accompanied by his younger brother Drusus, who proved to be a worthy companion. Tiberius himself demonstrated outstanding qualities as a commander: careful treatment of soldiers, willingness to share all the hardships of campaign life, and prudent caution as a strategist. Drusus, following his elder brother's example, earned the same loyalty among the soldiers. Their joint efforts culminated in complete success: the Roman borders in the north were extended to the Danube.

Augustus highly valued the military talents of both brothers. Soon, Tiberius, as consul, was tasked with continuing the campaign in Pannonia, where he replaced the suddenly deceased Agrippa — his mentor and father-in-law. This fact testified to Tiberius's recognition as Augustus's best military leader. From 12 to 7 BC, despite fierce resistance from the Breuci and Dalmatians, Tiberius completely subdued Pannonia and expanded the Danubian territories of the Empire. Meanwhile, Drusus reached the Elbe in Germany.

Problematic Heir

In 12 BC, Agrippa, the most likely successor to Augustus, died, after which Tiberius found himself among the potential heirs. To secure this status, the emperor insisted that Tiberius divorce his wife Vipsania, the mother of his son Drusus, and marry Octavian's daughter and Agrippa's widow, Julia. The relationship between the forced spouses did not work out, and Julia became known for her disdain for her new husband and open infidelities. She considered her own children by Agrippa — Gaius and Lucius — as potential heirs.

In 9 BC, Tiberius's brother Drusus died in his arms after a fall from a horse during the German campaign.

The divorce from his beloved woman and marriage to an unloved one, the death of his brother, and competition from younger rivals undermined Tiberius. In 6 BC, despite being a tribune and the de facto co-ruler of Augustus, Tiberius unexpectedly withdrew into voluntary exile on the island of Rhodes.

For some time, he continued to be perceived as a significant political figure, but in 1 BC, his tribune powers expired, and Tiberius completely lost political influence. His requests to return to Rome as a private citizen were consistently rejected by the offended Augustus.

However, at the turn of the era, another unexpected twist of fate occurred. In 2 AD, Julia's scandalous reputation finally led to her exile, after which Tiberius, as a private citizen, finally returned to Rome. In the same year, Lucius died of illness, and in 4 AD, Gaius died in Armenia. Rumor attributed responsibility for these deaths to Livia, who was clearing the path to the principate for her own son. Augustus indeed had no heirs left except Tiberius.

In the same year, the emperor officially adopted Tiberius, who in turn adopted his nephew Germanicus — the son of the late Drusus. Tiberius once again became a tribune, and in addition, the imperium — the highest military authority — was extended to him.

As a successor, Tiberius once again went to war — leading the suppression of the Great Illyrian Revolt of 6-9 AD. As Suetonius noted: "He was entrusted with this war — the most difficult of all Roman wars with external enemies after the Punic Wars." Tiberius quickly redeployed legions from other provinces and completely suppressed the revolt, restoring Roman control over Illyricum and Pannonia.

Barely finishing the Illyrian campaign, Tiberius received news of the disaster in the Teutoburg Forest, where three legions under the command of Quintilius Varus were destroyed. He immediately went to Germany, where he managed to stabilize the situation and strengthen the Rhine border, although full control over the region could not be regained.

On August 19, 14 AD, Emperor Augustus died, and Tiberius finally became princeps himself. Despite their complex personal relationship, Augustus made a wise choice — his successor was a 56-year-old experienced statesman and military leader with an impeccable reputation. The transfer of power went smoothly — the Senate, army, and magistrates swore allegiance to the new princeps without any issues.

The Beginning of the Reign

In his time, Augustus led Rome as a result of victory in a series of civil wars that had tormented Rome for several decades. Ending this bloody era, he proclaimed the "restoration of the Republic."

Despite Tiberius's authority, the very principle of hereditary transfer of power still caused confusion among the uninitiated Romans, so the new princeps demonstratively emphasized his commitment to republican traditions. Suetonius quotes the emperor's characteristic words: "I have often said and repeat, senators, that a good and benevolent ruler, entrusted with such extensive and complete power by you, must always be a servant to the Senate, sometimes — to the entire people..." Tacitus, however, explains this position as political calculation: "He tried to hide the true meaning of his motives as deeply as possible."

Both historians describe in detail the scene of Tiberius's refusal of power, supposedly agreeing to take the reins of government only after the Senate's persistent persuasion. In their account, Tiberius sincerely tried to share power with the senators, but they voluntarily refused. A very telling detail.

Reserved and cautious by nature, Tiberius well understood the risks of the princeps position, as he had witnessed numerous conspiracies against Augustus. Apparently, the new emperor genuinely sought to share the burden of responsibility with the Senate, not wanting to become the sole target for criticism in case of political failures. Moreover, the publicity inevitably accompanying the position of the "first citizen" clearly weighed on him. Tiberius became princeps more out of a sense of duty than a thirst for power. Tacitus is perhaps unfair here.

Tiberius began his reign by diplomatically resolving the mutinies of legionaries in Pannonia and Germany, who had been delayed in receiving their pay. Subsequently, timely payments became a hallmark of his policy, as the emperor understood well what power depended on.

His financial policy was equally balanced. The emperor reduced large-scale construction and limited funding for lavish games, aiming to stabilize state finances, depleted after the Illyrian uprising and German campaigns. At the same time, he wisely lowered taxes to increase their collectability — an atypical measure for those times. Explaining his tax policy, Tiberius said: "A good shepherd shears his sheep, but does not flay them". He left a full treasury to his successor Caligula.

Stable finances favored social policy: generous distribution of grain, control over food prices, and large-scale assistance in case of disasters. Although in the classic formula "bread and circuses" the latter were rather lacking due to Tiberius's frugality, but there was no shortage of bread.

Guided by principles of economy and caution, the emperor abandoned Augustus's expansionist policy. During Tiberius's entire reign, the empire did not engage in any conquest wars, except for German punitive expeditions by his stepson Germanicus. Instead of military adventures, Tiberius preferred diplomacy. For example, in 36 AD, he once again placed a loyal person on the Armenian throne and secured recognition from Parthia.

The Illyrian uprising deeply impressed Tiberius, showing that excessive exploitation of provinces could lead to a large-scale rebellion. The emperor tightened control over governors and, as mentioned above, reduced the tax burden. However, these measures reduced his popularity among senators and equestrians. For the senatorial class, plundering provinces was a traditional source of income, and equestrian publicans lost part of their profits from tax collection. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of such a policy is evident: no uprisings comparable to the Illyrian one occurred under Tiberius.

However, in historical memory, Tiberius, unfortunately, remained not as a wise administrator.

Consolidation of Power

The main weakness of the princeps was a lack of charisma. Unlike Augustus, who skillfully built his image and masterfully played to the public, Tiberius either underestimated the importance of propaganda or simply did not possess the necessary qualities. He seemed to deliberately minimize his public presence, appearing in public only when absolutely necessary.

One of Tiberius's most important reforms was transferring the right to elect and judge magistrates from popular assemblies to the Senate. The reserved emperor found it much more comfortable to control senators behind the scenes than restless plebeian gatherings. Paradoxically, the formal strengthening of the Senate simultaneously led to the strengthening of sole imperial power.

Tiberius methodically consulted with senators on all important issues but never clearly expressed his own opinion. This strategy provoked endless strife among senators, preventing the formation of a unified opposition. The law on insulting majesty was most often applied by the senators themselves against each other. The emperor himself preferred to spend time outside Rome, away from prying eyes. His "right hand" in the capital became the commander of the Praetorian Guard (Praetorian Prefect) Lucius Aelius Sejanus.

In 19 AD, his nephew and adopted son Germanicus suddenly died, and in 23 AD, his biological son Drusus died. Rumor attributed Germanicus's poisoning to Tiberius himself, and Drusus's death was blamed on his widow Livilla, who had entered into a love affair with Sejanus. Now potential successors became one of the young children of both deceased. Parties of supporters of the Germanicus family, led by his widow Agrippina, and the Drusus family, led by his widow Livilla and her lover Sejanus, emerged.

In 26 AD, Tiberius additionally quarreled with his mother Livia and finally withdrew to the island of Capri off the coast of Campania. Isolation on the island was his usual reaction to emotional turmoil.

"The Recluse of Capri"

Fearing that young heirs would not be able to withstand senatorial opposition, Tiberius began systematically "cleansing" the Senate. The law on insulting majesty was applied more frequently, and the main executor of repressions in Rome was, of course, Sejanus. Having removed himself from affairs, the emperor gradually lost control over the capital, becoming dependent on the Praetorian Prefect. Sejanus, apparently, either aimed to become a successor himself or hoped to become a regent for the young Gemellus — the son of Drusus and Livilla.

As part of the fight against supporters of the Germanicus family, Sejanus exiled his widow Agrippina, and his children Nero and Drusus were imprisoned, where Nero either committed suicide or died of hunger in 31 AD. Only the youngest son of Germanicus, known by his nickname "Little Boot" — Caligula, was not subjected to repressions.

Finally, the Praetorian Prefect went all-in and, together with Livilla, organized a conspiracy against the emperor himself. However, the conspiracy was uncovered, leading some authors to suggest that Tiberius initially manipulated Sejanus to deal with the Germanicus family through his hands and then "disposed" of the executor. In 31 AD, Sejanus was arrested right during a Senate session by the new Praetorian Prefect Quintus Macro and immediately executed. Livilla either committed suicide or was sent to her mother's house, where she was starved to death.

The plot with Sejanus's conspiracy heightened Tiberius's natural caution, which finally turned into paranoia. The period from 31 to 37 AD became the peak of repressions and trials for insulting majesty. Despite the death of the leaders of the Drusus family party — Livilla and Sejanus, Tiberius did not spare the disgraced leaders of the Germanicus family party. In 33 AD, Agrippina and her son Drusus died of hunger in prison.

However, it is important to understand the real scale of the repressions. Tacitus reports about 50-60 executed, while Suetonius mentions about a hundred. The victims of selective terror were exclusively representatives of the privileged senatorial and equestrian classes.

Despite its moral dubiousness, Tiberius achieved the main goal — he cleared the entire political field of opposition for his successors. In 37 AD, the emperor intended to return to Rome, but fell ill on the way and died at the age of 77. The principate passed without any resistance to the joint rule of the last remaining men from both parties: Drusus's son — Gemellus, and Germanicus's son — Caligula. The latter, with Macro's support, practically immediately seized real power and soon forced his co-ruler to commit suicide.

Dio Cassius gave a remarkably accurate characterization of Tiberius: "He was a man with many good and many bad qualities, and when he displayed the good, it seemed that there was nothing bad in him, and vice versa." Indeed, his frugality, caution, and asceticism provided the state with financial stability and peace in the provinces. However, the same caution, which turned into paranoia, led to a regime of terror.

Tiberius's reign became a watershed in the history of the principate. If Augustus, enjoying unquestionable authority, still maintained the illusion of co-ruling with the Senate, Tiberius, by the end of his reign, clearly demonstrated that the Senate now depended solely on the will of the princeps.

Take the test on this topic

History

Tiberius: Emperor Against His Will

This is the story of a cynic, misanthrope, and sociopath at the head of Rome. Solidify your knowledge about him!