Article

Antony and Cleopatra

Antony

Mark Antony was born either in 86, 83, or 82 BC and came from the ancient and influential plebeian family of the Antonii, whose members participated in drafting the Law of the Twelve Tables as early as the 5th century BC. His grandfather, Mark Antony the Orator, was a consul and then a censor of the Senate. However, crises and turmoil did not bypass the family— the Orator was killed as a result of Marius's repressions because he sided with Sulla. Mark Antony's parents were forced to hide from persecution, which is why the exact place and year of his birth are unknown.

Antony's early years fell during a relatively peaceful time after the war between Marius and Sulla. The young man was not deprived of beauty and physical form, possessed a bright charisma, and spent his youth in "drunkenness, debauchery, and monstrous extravagance," as Plutarch wrote. For the Romans, it was not a vice to indulge in passions in youth, but in adulthood, it was deeply condemned. Like any Roman aristocrat, Antony received a good education and, like his grandfather, excelled in oratory, which even his future enemy Marcus Tullius Cicero noted. However, while Cicero belonged to the conservative "Attic" school, emphasizing facts and precision, Antony belonged to the "Asiatic" school, emphasizing spectacle and clarity.

His high birth allowed Antony to take the position of prefect of the cavalry in the troops of the governor of Syria, Aulus Gabinius, where he commanded 400 to 500 cavalrymen. Together with Gabinius, he went to Judea, where he participated in suppressing a rebellion in the vassal kingdom. Antony captured the rebellious Judean king Aristobulus II and his son, and for storming the fortress of Sartaba, he was awarded the honorary military decoration "corona muralis" ("mural crown"), which was given to the first soldier to climb the walls of a besieged city. Antony proved himself as a talented commander and gained popularity among the soldiers, which he would not lose until the fateful Battle of Actium.

In 58 BC, in Egypt, Princess Berenice overthrew King Ptolemy XII Auletes, and the latter asked Rome for support. The Senate refused, and then the king offered a huge bribe to the commander of the Roman troops, Gabinius. Going against the Senate was a risky undertaking, and Gabinius hesitated. Antony persuaded the commander to take the gamble, and in 56 BC, he invaded Egypt, defeated Berenice, and restored Ptolemy to the throne. Antony actively defended the local residents against the embittered Ptolemy and even buried Berenice and her husband with royal honors, earning the love of the Egyptians. In 54 BC, after his term ended, Gabinius returned to Rome, where he was convicted of disobeying the Senate and exiled. Antony managed to avoid persecution.

Nevertheless, Antony had no desire to stay in Rome, and Gaius Julius Caesar, who needed talented commanders for the Gallic War, came to his aid. Antony accepted the offer. In Gaul, he served as a legate, that is, a legion commander, and carried out important assignments for Caesar. In 50 BC, Antony was elected a tribune of the people and represented the commander's interests in Rome. He attempted to veto the Senate's decision to declare Caesar an outlaw, but under threats of violence, he was forced to leave the Eternal City. In 49 BC, Caesar crossed the Rubicon and began another civil war.

In the struggle against Pompey the Great, Antony enjoyed Caesar's special trust, who, having assumed the position of dictator, appointed his associate as the commander of the cavalry, that is, his deputy. In 48 BC, Antony participated in the decisive Battle of Pharsalus, in which Pompey's forces were completely defeated. In his absence, the dictator entrusted the management of Rome to Antony. Taking advantage of his high position, he began to live lavishly: he confiscated Pompey's villa and led a luxurious lifestyle while harshly managing the city, which, in the difficult times of civil war, provoked the anger of the Romans. Caesar realized that Antony was more of a hindrance than a help and for a time, he fell out of favor. However, Antony's talents outweighed his shortcomings, and Caesar secured his election as consul. It was in this position that Antony met the fateful Ides of March in 44 BC.

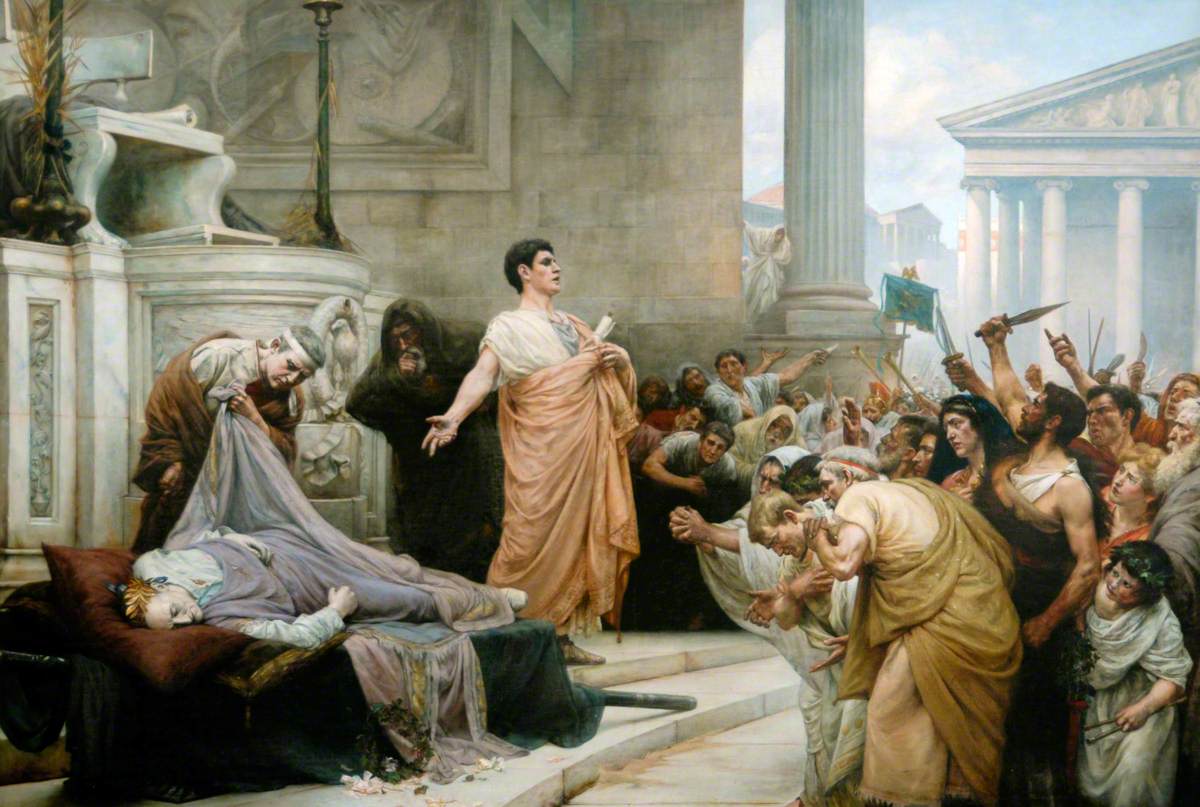

Antony was with Caesar on the day of the assassination. However, he was not in the Senate building at the crucial hour and failed to save the dictator from the numerically superior conspirators. The Caesarian camp rallied around Antony as the most prominent supporter of the dictator, and many insisted on the execution of Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. However, the new leader sought a truce with the conspirators, knowing about the republican opposition in the Senate.

Only after consolidating forces did he enter into conflict with the Senate and Caesar's adopted son Octavian, but soon they united and, together with Lepidus, formed the Second Triumvirate to fight the republicans and Caesar's murderers. Cicero was beheaded, and Brutus and Cassius met their deaths in 42 BC at the Battle of Philippi.

The Second Triumvirate divided the provinces of the Republic. Antony, as the leading figure, received the wealthy East with Gaul, and he departed to Cilicia on the southern coast of Asia Minor to restore order. For this purpose, in 41 BC, he summoned Cleopatra to confirm the agreements between Rome and Egypt. At that time, Egypt was the largest of the eastern states subordinate to Rome, supplying grain to the Eternal City. Before meeting Cleopatra, Antony was already one of the leading figures of the Republic and an outstanding military leader, but his fate changed dramatically after becoming closely acquainted with the Egyptian queen.

Cleopatra

The last ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt was born at a very difficult time for her state. Hellenistic Egypt, once founded by Alexander the Great's general Ptolemy Soter, was in decline—constant internal strife among Ptolemy's descendants led the country to heavy defeats by the Seleucid kingdom and dependence on Rome.

Cleopatra was born in 69 BC, being the second daughter of the aforementioned Ptolemy XII Auletes. Cleopatra's father was not an outstanding politician, preferring festivities and revelry to state affairs, which were costly to the royal treasury. Cleopatra grew up in an atmosphere of court intrigues and constant palace coups. The princess received an excellent education, was not lacking in intelligence, spoke nine (!) languages fluently, and the environment of the Ptolemaic court nurtured her into a cunning intriguer. The future queen of Egypt, judging by surviving sculptural portraits and coin images, was not an unparalleled beauty as depicted in films, but she possessed a captivating charisma and charm that allowed her to get her way. Plutarch gave a good description of the queen's talent:

"For the beauty of this woman was not that which is called incomparable and strikes at first sight, but her conversation had an irresistible charm, and therefore her appearance, combined with the rare persuasiveness of her speech, with the enormous charm that shone in every word, in every movement, was deeply imprinted in the soul. The very sounds of her voice caressed and delighted the ear, and her language was like a multi-stringed instrument."

[Plutarch, Antony, 27]

Ptolemy XII Auletes died in 51 BC, and the throne was inherited by Cleopatra VII along with her younger brother Ptolemy XIII. According to Egyptian custom, Cleopatra married her brother and became his co-ruler. However, a power struggle soon erupted between them. Cleopatra was forced to flee Alexandria but did not give up her ambitions. Caesar came to the young queen's aid.

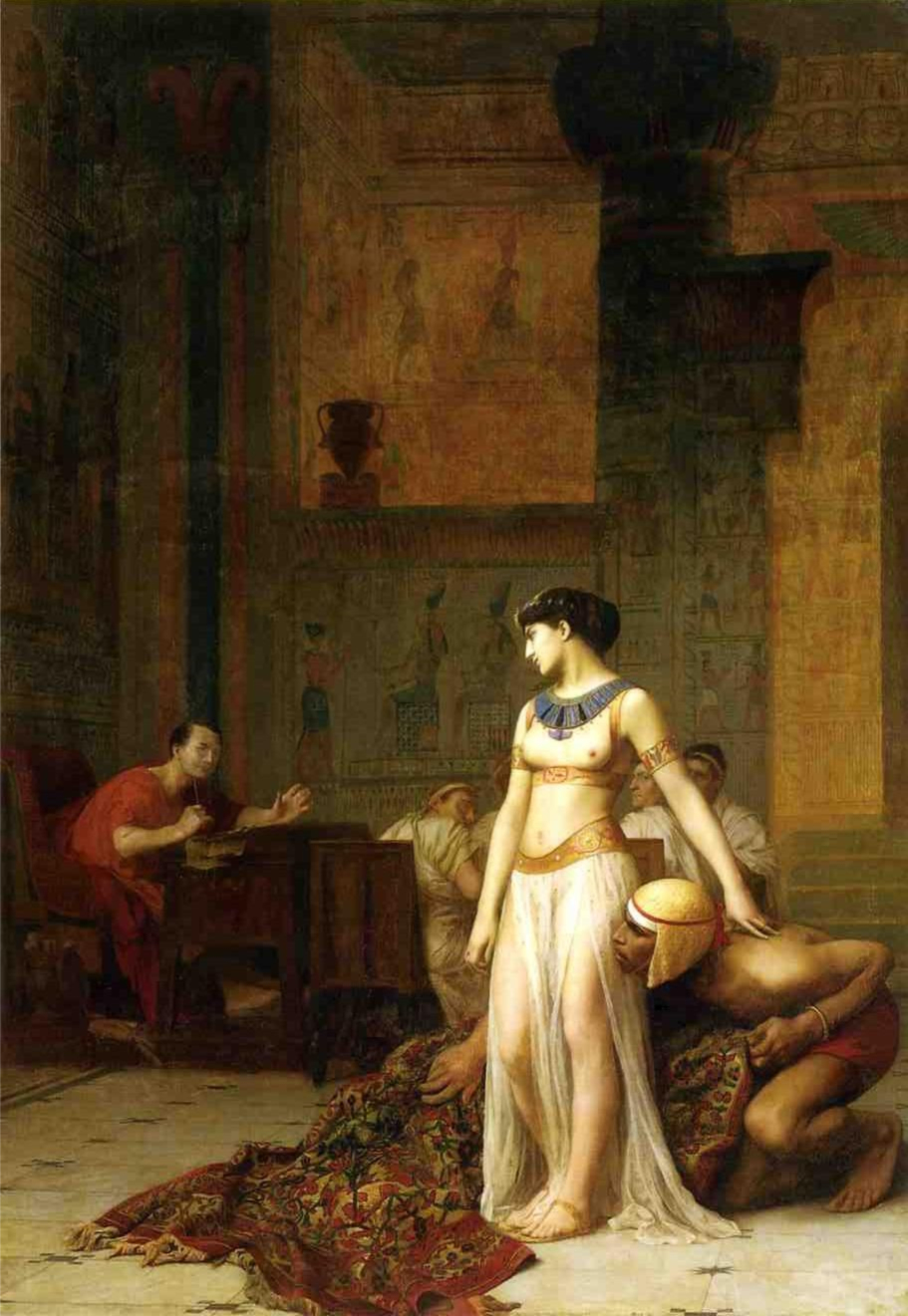

After the fiasco at Pharsalus, Pompey was forced to flee to Egypt in search of support but was killed at the initiative of Ptolemy XIII's supporters to win Caesar's favor. Caesar arrived in Egypt following Pompey but was enraged when he learned of such an end for his enemy—it was not for the Egyptians to decide the fate of a Roman citizen, no matter who he was.

Then Cleopatra's supporters secretly brought the queen to Caesar, hidden in a bed sack. The 52-year-old dictator was charmed by the intelligence and charisma of the 22-year-old queen, and he fully sided with her. Ptolemy XIII died in street fighting, and Cleopatra began to rule jointly with her other brother, Ptolemy XIV, although the real power belonged to her alone.

Many researchers, such as Soviet historian S. L. Utchenko, consider Caesar's Alexandrian War a pure gamble, driven only by the "demonic charm" of the Egyptian queen. Without denying her allure, the author still believes that there was political calculation in this alliance—Caesar sought a ruler in Egypt personally dependent on him to ensure uninterrupted grain supplies to Rome. The queen likely understood her significance and sought to extract the maximum from the circumstances. Thus, both combined the pleasant with the useful.

Cleopatra and Caesar had a son, Ptolemy XV Caesarion—"little Caesar." The queen came to Rome, where she immediately earned the dislike of the Roman public—it was believed that the Egyptian woman had a bad influence on Caesar and abused his favor. Republicans saw monarchical tendencies in the romance and became even more suspicious of his aspirations for royal power. After Caesar's assassination in 44 BC, Cleopatra returned to Egypt, where she likely poisoned her brother Ptolemy XIV to make her son Caesarion her co-ruler.

In the ensuing war between the Caesarians and the Republicans, she took a dual position—on one hand, she sent a fleet to help the Caesarians, which, however, was shipwrecked en route, and on the other, she did not interfere with the Roman legions in Egypt coming to Cassius's aid, although she could hardly have prevented them from doing so, given the deplorable state of the Egyptian army. In any case, in 41 BC, Cleopatra made every effort to win Antony's favor.

The Alliance of the Queen and the Triumvir

Cleopatra's task was complicated by the fact that by 41 BC, Antony was already married for the third time to Fulvia, with whom he had a warm relationship, and it seems the spouses truly loved each other. Nevertheless, it was known that Antony had a weakness for women and would not refuse a fleeting affair with the queen. But Cleopatra set herself a much greater goal—to make Antony fall in love with her.

The queen arrived at the triumvir on a luxurious galley in the image of Aphrodite. This spectacle impressed Antony, and he indeed fell in love with Cleopatra. The winter of 41–40 BC, the triumvir spent with her in Alexandria, forgetting all affairs in a passionate romance.

Meanwhile, discontent with the rule of the Second Triumvirate was brewing in Rome. Antony's brother Lucius, along with his wife Fulvia, raised a rebellion against Octavian in Italy, fearing that he was pushing his associate out of power. Antony, to his displeasure, was forced to return to the Apennine Peninsula to resolve the situation. However, even before his arrival, Lucius and Fulvia were defeated at the city of Perusia, giving the conflict the name of the Perusine War. Soon Fulvia died, and in 40 BC, Antony, to strengthen the alliance with Octavian, married his widowed sister Octavia. The triumvirs also redistributed the provinces. Antony was forced to give Gaul to Octavian, thereby completely handing over the western provinces to the latter. Lepidus was effectively removed from power but nominally retained Africa.

Antony could not immediately return to Cleopatra, as his attention was diverted by the Parthian invasion, which he dealt with until 37 BC. All this time, his lawful wife Octavia accompanied him, impressing those around her with her virtue and devotion—the marriage even produced two daughters. Nevertheless, Antony sent his wife back to Rome and, after the military actions, summoned his royal lover to officially marry her according to Egyptian custom. In effect, Antony abandoned his lawful wife and the sister of his ally. Appian of Alexandria wrote that "Cleopatra possessed Antony."

Antony then officially recognized his children with Cleopatra—twins Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene—and then transferred Cyprus, most of Phoenicia, Cilicia, Nabataea, and Coele-Syria to Egypt's control. The benefits for Cleopatra are obvious—reclaiming the former Ptolemaic territories back to their kingdom, but from Antony's side, this step seems completely unreasonable and cannot be explained solely by gaining loyalty from Egypt.

Afterward, Antony embarked on a campaign against Parthia to build on recent military success. The campaign ended in defeat—the Roman troops did not achieve success and suffered serious losses. To somehow save face, the triumvir defeated Armenia, which had sided with Parthia, and to present his unsuccessful campaign as a victory, he celebrated a triumph, but not in Rome as was customary, but in foreign Alexandria with Cleopatra. In 35 BC, this triumph took place with all the eastern pomp, and the couple appeared before the Alexandrian crowd in the images of Dionysus and Isis.

For years remaining in the East, Antony lost touch with the Roman public. Actively courting the local population, he did not shy away from deifying his power—in Ephesus, the Greeks called him Dionysus, and the Egyptians considered him Osiris. Antony officially recognized Caesarion, Caesar's son by the foreign queen, as the late dictator's heir, and proclaimed his children with Cleopatra as rulers of several eastern provinces. Partly, such a policy was predetermined by geography, as Octavian received the western provinces, where Romanization had advanced significantly further, while Antony received the more monarchic East. Nevertheless, the triumvir was excessively tempted by the East and the Egyptian queen, which Octavian did not fail to exploit.

In his propaganda, he openly accused Antony of embezzling the property of the Roman people, his provinces, in favor of Egypt, and presented the ambition to move the capital from Rome to Alexandria, as Antony inexplicably decided to celebrate his triumph in Egypt. Octavian also used the story of his sister for propaganda purposes—the virtuous Octavia, faithful to her lawful husband and raising their children, cast a shadow on Antony's marriage to Cleopatra. Thanks to Octavian's skillful propaganda, the queen appeared to the Romans as a homewrecker who had bent the once-popular general to her will.

Antony began to lose supporters and could no longer influence the situation in the metropolis. Octavian even here proved himself a shrewd politician and declared war not on Antony but on Cleopatra, leaving the triumvir no choice but to stand up for the foreign queen.

In 31 BC, Antony and Cleopatra were defeated in the naval battle at Actium. After the defeat, they fled to Alexandria, where they spent their remaining time in desperate hedonism, organizing the "Society of the Inimitable Livers," which included the couple themselves and their servants. In 30 BC, when Octavian's troops approached the city, Antony, receiving false news of Cleopatra's death, committed suicide by falling on his sword. The queen, learning of her husband's death, also committed suicide, according to legend, allowing a poisonous snake to bite her. Caesarion was killed by Octavian's order, and the other children were given to Octavia to raise.

Egypt became a Roman province, and Octavian became the sole ruler of Rome with the title of Augustus. The eccentric and passionate Antony suffered a complete defeat before his cold and calculating rival.

Marriage to a foreign queen proved fatal for Antony's reputation. Cleopatra had already provoked the anger of the Romans and suspicions of aspirations for royal power during Caesar's time, and Antony seemed to be repeating the fate of his late patron. Nevertheless, marriage to the queen alone could not be the cause of the fall of such a figure. Playing at being a king and self-deification worked well in the East, but the Romans could not accept such behavior. They were outraged by Antony's monarchical tendencies and his extravagance towards Egypt.

In contrast, Octavian emphasized his "Roman-ness," his commitment to the interests of the Roman people, and their traditions, so his confrontation with Antony appeared not as a struggle for power but as a struggle of Rome against the eastern threat. One could say that Octavian completely won the information war and played on the national feelings of the Romans, forgive the author for such an anachronism.

The Romans, accustomed to republican rule, did not accept Antony, who openly imitated eastern kings. They wanted to see a living Republic, and Octavian gave them this illusion in the form of the Principate—his own autocracy, carefully disguised as a "restored Republic."

The image of Antony and Cleopatra in Roman historical memory was well summarized by Dio Cassius in his "Roman History":

"Antony was second to none in fulfilling his duty, but he committed many follies; at times he was extraordinarily brave and at the same time often failed due to his cowardice, he was sometimes great in spirit, sometimes insignificant; he seized others' goods, squandered his own, forgave some without any reason, and punished many unjustly. Therefore, although he became all-powerful from insignificance, a rich man from a pauper, neither benefited him, and he, hoping to become the sole ruler of the Romans, ended his life by suicide.

Cleopatra knew no bounds in either love passion or acquisitiveness, was ambitious and power-hungry, and also haughty and daring. She achieved royal power in Egypt through love charms, but hoping to achieve dominion over the Romans in the same way, she miscalculated and lost what she had. She subjected two of the greatest Romans of her time to her power, and because of the third, she ended her own life. Such were Antony and Cleopatra, and thus they ended their lives."

[Dio Cassius, Roman History, LI, 15]

Take the test on this topic

History

Antony and Cleopatra

Fascinated by the tragic love story of Antony and Cleopatra? We invite you to take the quiz!