Article

GERMAN NATIONAL PEOPLE'S PARTY (DEUTSCHNATIONALE VOLKSPARTEI)

In the Kaiserreich, the conservative monarchist camp was divided into several parties and movements. There was the German Conservative Party, which represented the interests of Prussian nobles and landowners from the eastern agrarian part of the country. This segment of the conservative camp was critical of the country's industrialization and urbanization due to the mass labor migration from villages to cities. Moreover, the growth of industry led to entry into global markets, and economic liberalism meant the removal of customs barriers – cheap Russian and American grain flooded into Germany, with which Prussian landowners had to compete in the domestic market. Many agrarian conservatives valued Prussia more than a "unified Germany."

Simultaneously, there was the Free Conservative Party, also known as the German Imperial Party, which represented the interests of heavy industry and state officials. These individuals, on the contrary, welcomed the creation of a unified German Empire, supported the industrialization and urbanization of the country, and the expansion of its economy into global markets.

Additionally, there were supra-party right-wing associations, the most famous and influential of which were the Landbund and the Pan-German League. The Landbund was a lobbying community of Prussian landowners. Closely associated with it, the Pan-German League advocated for imperialist expansion in overseas colonies and Eastern Europe. Both organizations demanded the ruthless assimilation of ethnic minorities, such as Poles, and openly opposed Jews.

During World War I, the conservative camp in Germany rallied around ambitious annexationist demands. The right-wing called for fighting until complete victory to seize as much territory as possible – in the West, East, and colonies. Furthermore, supporters of these movements believed that the Kaiser’s government was not making sufficient efforts for victory, and the home front required "cleansing" from liberals, socialists, and Jews.

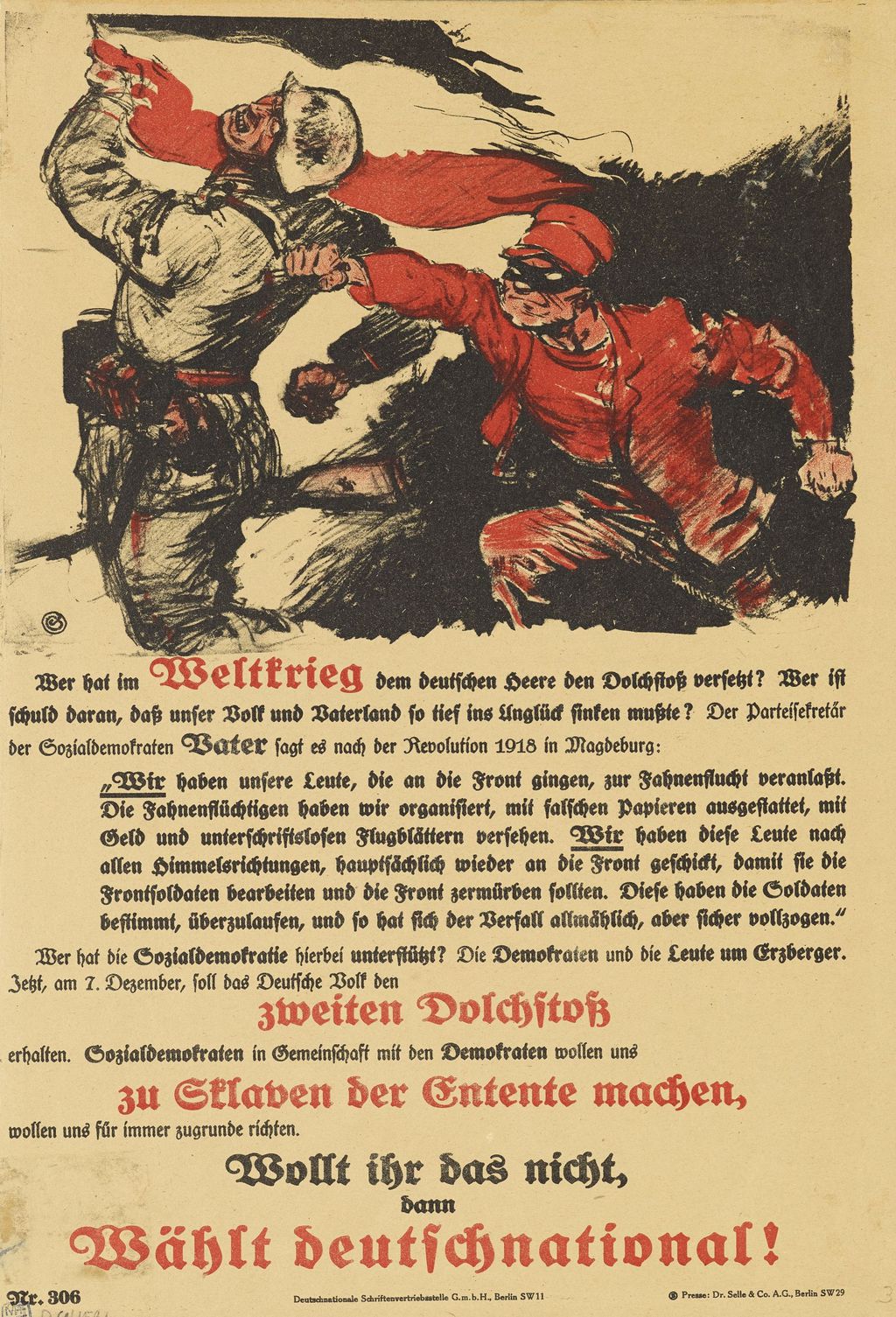

The outcome of the war turned into a bitter disappointment for the conservatives. It was in these circles that the "Stab-in-the-Back Legend" quickly emerged – the notion that Germany had every chance of victory but capitulated solely because oppositionists and Jews undermined the home front and instigated a revolution.

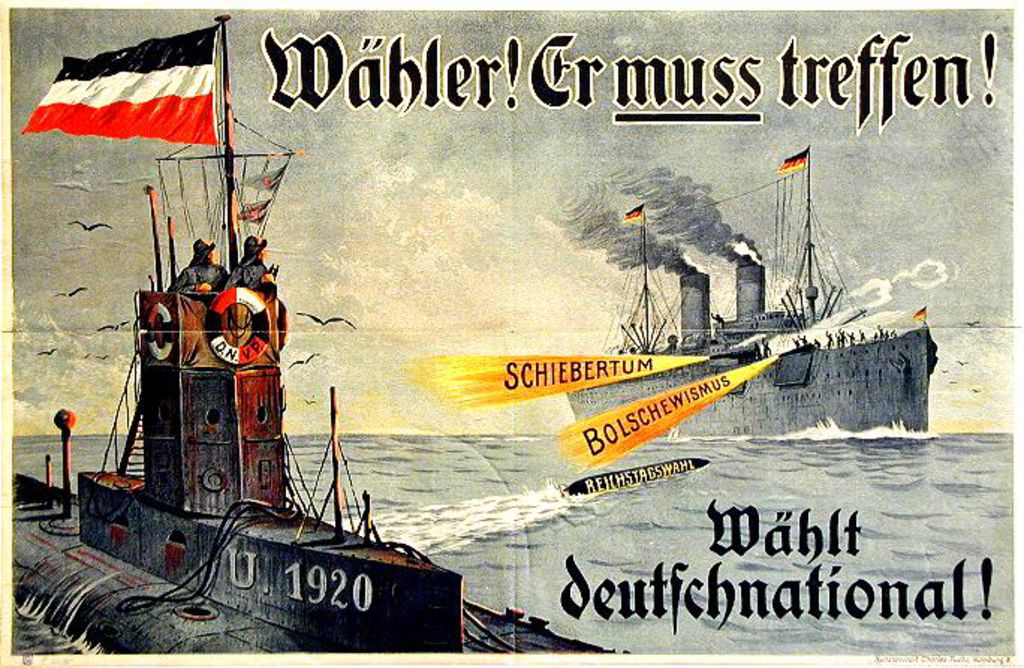

Revolutionary upheavals united the disparate conservative monarchist movements, and by December 1918, the German National People's Party (DNVP) was formed. It advocated for the restoration of the monarchy, possibly through a preliminary stage of right-wing dictatorship, a complete revision of the Treaty of Versailles, cessation of reparations payments, and protective tariffs to safeguard domestic producers. Additionally, it was a party of cultural and social conservatism, as well as militant anti-Semitism – Jews were seen as the main culprits of Germany's woes.

The social and geographical base of the DNVP became the Prussian agrarian regions east of the Elbe – they accounted for up to 40% of its entire electoral base. However, the party extended its influence far beyond East Elbia. Besides Prussian agricultural producers, the DNVP garnered support from large entrepreneurs, especially in the coal mining and metallurgical industries, who were interested in government contracts due to the militarization of the economy. The party also found its voters among Protestant employees and officials in the north and west of the country. DNVP supporters were plentiful among the "academic class," and as a party of cultural and social conservatism, it was particularly popular among Protestant housewives.

In March 1920, many DNVP members supported the Kapp Putsch, when volunteer corps briefly seized Berlin and overthrew the "Weimar Coalition" government. However, the coup quickly failed, and the party distanced itself from it.

The critical attitude towards the republic from the "right" eventually led to electoral successes – some voters became disillusioned with liberal parties and began voting for conservatives. If at the peak of the revolution in January 1919 the DNVP garnered 10% of the votes, by June 1920 it received 15% of the votes, and by 1924 this number increased to 20.5%. For most of the 1920s, the DNVP was the second most popular party in Germany after the Social Democrats. An important success for the monarchists was the election of the Kaiser’s Field Marshal and Chief of Staff during World War I, Paul von Hindenburg, as president of the republic. In 1925 and 1927 – 1928, the party even joined the ruling coalition alongside the Center, liberals, and Bavarian regionalists.

By the late 1920s, a split emerged within the DNVP between those who continued to uphold the principle of irreconcilability towards Weimar and those who reconciled and became "republicans by reason" ("Vernuftrepublikaner"). Among the latter was the party leader Count Kuno von Westarp, under whom the party twice joined republican cabinets. He indicated that monarchical loyalty could be transferred to President Hindenburg, and the DNVP's goal should be to solidify the conservative character of the republic.

However, the radical wing of the DNVP rallied around media magnate Alfred Hugenberg. In 1928, he took advantage of the party's declining results in the Reichstag elections from 20.5% to 14% – the DNVP lost some popularity after participating in the government coalition. Under the pretext of electoral failures, Westarp was ousted, and Hugenberg became the party leader, returning the DNVP to a principled anti-republican course.

Small groups of moderate conservatives left the DNVP and formed several minor parties – the Conservative People's Party, the Christian National Peasant and Farmer's Party, and the Christian Social People's Service. None of them achieved electoral success.

Hugenberg established the "Führer principle" in the "purified" DNVP, which implied single leadership and absolute subordination to the party leader. Additionally, he established cooperation with the "Steel Helmet" – a paramilitary organization of conservative anti-republican front-line soldiers.

Hugenberg's first significant action as party leader was the initiative to hold a referendum against the Young Plan – an international agreement under which Germany's annual reparations payments were reduced in exchange for their extension until 1988. Nationalists demanded the plan not be accepted and to unilaterally refuse any payments. To attract public attention to his initiative, Hugenberg involved other revanchist forces in the referendum campaign, such as the small National Socialist German Workers' Party and its leader Adolf Hitler. The referendum in December 1929 failed because most voters ignored it, but the Nazis used it to increase their notoriety.

With the onset of the Great Depression, conservatives became the main victims of the rise of Hitler's party. From 14% of the vote in 1928, the party plummeted to 7% in 1930 and to 6% in July 1932.

In the autumn of 1931, Hugenberg attempted to unite the entire revanchist nationalist flank under his "Harzburg Front." But Hitler refused to recognize Hugenberg's leadership, and the joint front of Nazis and conservatives failed. In the spring 1932 presidential elections, the Nazis nominated Hitler, and the conservatives nominated one of the "Steel Helmet" leaders, Theodor Duesterberg. In the first round, Duesterberg received 7% of the votes, Hitler 30%, and the incumbent President Hindenburg 49.5%. After this, Duesterberg's candidacy was withdrawn.

Hugenberg's right-radical anti-government course alienated him from big industry, which preferred to support first the authoritarian right-centrist cabinet of Heinrich Brüning, and then General Kurt von Schleicher. The mass electorate shifted to the Nazis, so the last social support for the DNVP remained large landowners in the agrarian East Elbian regions. In their interests, Hugenberg advocated for protective tariffs and food import quotas. It was on this basis that he once again found common ground with the Nazis. The agrarian lobby persuaded the Prussian Junker Hindenburg to overlook prejudices and give the "plebeian" Hitler a chance.

On January 30, 1933, the president appointed Hitler as chancellor in a right-conservative cabinet. Of the twelve members of the government, six were non-partisan conservatives, three belonged to the DNVP, and three to the Nazi party. Hugenberg himself headed the combined Ministry of Economy, Food, and Agriculture. One of the "Steel Helmet" leaders, Franz Seldte, became Minister of Labor.

Conservatives hoped to overthrow Weimar with a "broad right coalition," in which Hitler would be merely a facade for the "plebeian" masses. But the Nazi leader proved to be a more cunning politician. The SA (Storm Troopers) were granted the status of "auxiliary police forces" and could now carry out "official" terror against all their political opponents. The "Steel Helmet" was given a similar status, but there were more vicious and active stormtroopers. The main constitutional rights and freedoms of individuals were suspended by a presidential emergency decree on February 28 after the Reichstag building was set on fire.

In an atmosphere of terror and intimidation, new parliamentary elections were held on March 5, in which the National Socialists received 43%, and the conservatives 8%. On March 23, the Reichstag, with a constitutional majority of votes, including the Center and liberals, voted to grant the government emergency powers to issue laws bypassing parliament.

Within a few months, Hitler managed to isolate Hugenberg in the cabinet. Left without any support, he resigned from all positions by June. Simultaneously, the DNVP was forced to dissolve itself. Some activists ceased political activity, while others, like Labor Minister Seldte, joined the Nazi party. The "Steel Helmet" lost organizational independence and by 1935 was fully integrated into the Storm Troopers.

Reasons for the ultimate failure of conservatives in the Weimar Republic:

The victory of the "irreconcilable" wing over moderate "republicans by reason," which placed the DNVP at the forefront of dismantling the republic with complete inability to somehow limit the Nazis;

The reputation of being an "old-fashioned," aristocratic, and monarchical party, which completely lost the battle for the broad masses of conservative voters to the more socially-oriented populists of the NSDAP;

The DNVP limited itself to confessional boundaries as a Protestant party, alienating a third of the country's Catholic population.

Some conservatives later became disillusioned with Nazism and even became activists of the anti-Hitler Resistance. Such were, for example, Carl Friedrich Goerdeler and Ulrich von Hassell. Both were activists of the July 20, 1944 plot and were executed after its failure.

After the war, most of the conservative electoral base in West Germany was absorbed by the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), which united Catholics and Protestants within a single right-centrist party. The unsavory reputation of the DNVP as an ally and helper of Hitler led the Christian Democrats to prefer relying on the legacy of the Center rather than German nationalists.

Some right-oriented activists attempted to revive the legacy of the DNVP in post-war West Germany and created the German Conservative Party – German Right Party. It even managed to elect several deputies to the first Bundestag, but its successes ended there. Subsequently, the party merged with other right-wing groups, but they no longer achieved success.

In the East, almost all the territories that were the electoral support of the DNVP were transferred to Poland and the Soviet Union after the war. There were no attempts to revive a conservative nationalist and monarchist party in the GDR.

Take the test on this topic

History

German National People's Party

Did you like the article? Now take the test and check your knowledge about the German National People's Party!