Article

CATHOLIC CENTER (ZENTRUM)

The historical ratio of Catholics to Protestants in unified Germany was approximately 30% to 70%. Catholicism predominated in the western provinces of Prussia on the border with France and the Benelux, in the southern states, and in the eastern provinces of Prussia on former Polish lands.

The creation of a unified German state led by Protestant Prussia prompted German Catholics to form their own party to more effectively defend their confessional interests. Thus, in 1870, the Catholic Centre Party was established.

The first decade of the German Empire was marked by the "Kulturkampf" – a struggle by the secular governments of the German states against the autonomous rights of the Catholic Church. Priests were banned from political propaganda, the clergy were deprived of the right to oversee schools, church appointments were handed over to state officials, civil marriage was introduced, and the Jesuit order was banned. However, all these repressive measures only united the Catholic community. By the late 1870s, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck considered socialists to be a greater threat to the internal security of the state than Catholics and ended the "Kulturkampf." Most of the restrictive laws, except for the recognition of civil marriages and the expulsion of the Jesuits, were repealed.

The Catholic Centre, united by a common confessional identity thanks to the "Kulturkampf," performed successfully in all subsequent parliamentary elections in the Kaiserreich. Most often, Catholics had the largest faction in the Reichstag. Limited by confessional boundaries, the Centre was a cross-class party – supported by all social groups of Catholic Germany from workers and employees to small and large property owners. Just as secularized social democrats created socialist trade unions, Catholics also began to form their own Christian trade unions in accordance with the social doctrine of the Roman Church.

After the end of the "Kulturkampf" and Bismarck's resignation, the Centre became more loyal to the Kaiserreich government, especially in foreign policy. At the beginning of World War I, Catholics, along with other parties, supported the "Burgfrieden" policy.

However, advocating for a "defensive war," the Centre, together with the Social Democrats and left-wing liberals, rejected the annexationist demands of the expansionists and insisted on an early end to the war through mutual agreement. The three parties established close cooperation and additionally began to demand the democratization of the regime. As a concession, in November 1917, a representative of the conservative wing of the Centre, Georg von Hertling, became the first "party" chancellor in German history.

The Centre accepted the November Revolution of 1918 and the overthrow of the monarchy. Party representative Matthias Erzberger became the head of the German delegation at the peace negotiations with the Entente in the Compiègne Forest and signed the armistice on November 11, ending World War I.

In the 1919 elections to the Constituent Assembly, the Centre consolidated the votes of the majority of the Catholic electorate and received 20% of the votes. Together with the Social Democrats (38%) and the left-liberal German Democratic Party (18.5%), it formed the "Weimar Coalition," named after the Thuringian city of Weimar, where the Constituent Assembly met. Centre deputies voted for the acceptance of the Treaty of Versailles and the ratification of the Weimar Constitution.

The main contribution of the Centre to the foundations of the state structure was its opposition to the unification of the Reich, advocated by the left-liberal authors of the Constitution. Germany remained a federation of autonomous "Free States" within their old "feudal" borders with their own governments, parliaments, and laws.

Nevertheless, Catholic Finance Minister Matthias Erzberger made a significant contribution to the economic centralization of Germany – he took away tax sovereignty from the disparate states and transferred it to Berlin. In retaliation for the financial reform, tax increases, and the signing of the "treacherous" armistice in Compiègne, ultra-right terrorists assassinated Erzberger in August 1921.

In the June 1920 elections, all parties of the "Weimar Coalition" lost a significant portion of their votes. The Centre's result fell from 20% to 13.5%, largely due to the separation of the Bavarian People's Party. From then on, the "Weimar Coalition" could no longer form imperial cabinets on its own, although it maintained its dominant position in Prussia until 1932.

However, the Centre, true to its name, remained at the center of the political spectrum and could form coalitions with both the left and the right. As a result, it was continuously a governing party from 1919 to 1932. Of the thirteen heads of cabinets that governed the country from November 1918 to January 1933, four were active representatives of the Centre. In the 1925 presidential elections, party chairman Wilhelm Marx became the consolidated candidate of the republican forces and received 45% of the votes in the second round, narrowly losing to Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, who received 48%.

The electoral base of Catholics in parliamentary elections remained stable, fluctuating between 12 and 13.5% of the votes. Nazism practically did not affect Catholic voters, who largely remained loyal to their old party.

However, the social base of the Centre gradually eroded due to urbanization and the subsequent secularization of city dwellers. By the late 1920s, the balance of power within the party shifted from the left wing, oriented towards maintaining the republican regime and cooperation with the Social Democrats, to the right wing, for which the cohesion of the confessional core was more important than other issues. The party leader became priest Ludwig Kaas, who publicly spoke of his support for the authoritarian restructuring of the republic.

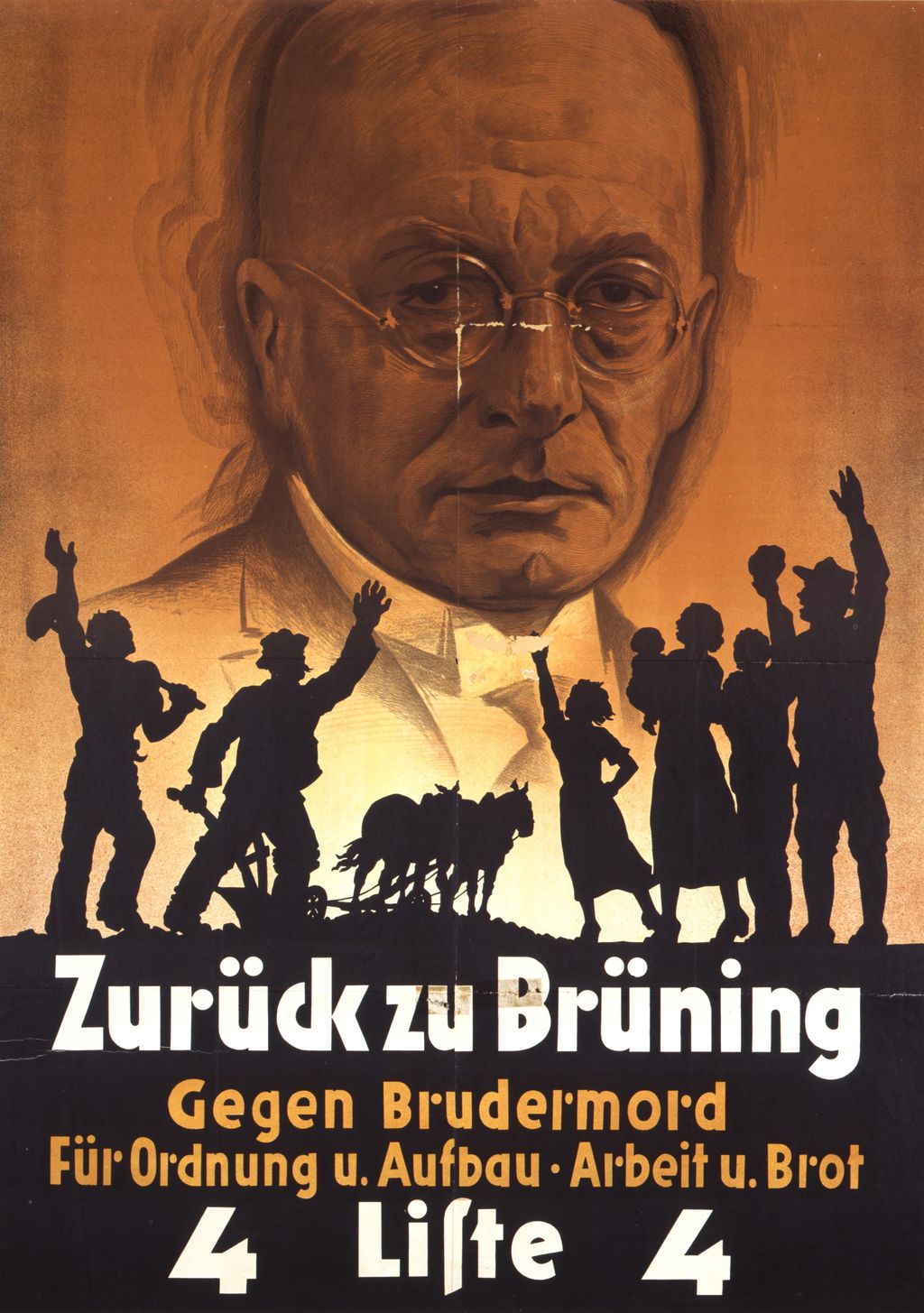

In March 1930, President Paul von Hindenburg appointed another representative of the Centre, Heinrich Brüning, as chancellor. Germany was already in the throes of the Great Depression, and Brüning believed that the best way to deal with it was to cut government spending and raise taxes. The country embarked on a harsh deflationary policy, leading to the impoverishment of large segments of the population and the rise of radical movements – Nazis and communists. In the opposition press, Brüning was nicknamed the "Hunger Chancellor." In contrast, Hindenburg publicly referred to the head of government as the "best chancellor since Bismarck."

Brüning also hoped to use the economic hardship to achieve the cancellation of reparations. And he succeeded! First, in 1931, a one-year moratorium on their payment was declared, and in the summer of 1932, reparations were effectively written off.

Economic historians suggest that within the country, the deflationary policy could have led Germany out of the Great Depression by the mid-1930s, provided Brüning's government had remained in power by then. But deflation sparked a political storm that the cabinet did not survive.

In April 1932, Brüning successfully stopped Hitler in the presidential elections and secured Hindenburg's re-election for a second term. However, by May, the chancellor fell victim to intrigues from conservatives. They were dissatisfied that Brüning continued to cooperate with the Social Democrats within the Prussian "Weimar Coalition." Additionally, the chancellor proposed confiscating unprofitable estates from the East Elbian Junkers for compensation and distributing land plots to the unemployed. Landowners considered this "agrarian Bolshevism" and complained about Brüning to Hindenburg, who himself came from this social class. Finally, the old president felt resentment that the chancellor had made him a candidate from the moderate left rather than the right during his re-election. The culmination of all these accumulated grievances against Brüning was his resignation.

The new head of government was another Centre member, Franz von Papen. However, he had no strong ties with the party organization and electoral base, which remained loyal to the previous chancellor. Within a few days, Papen was expelled from the party for "betraying" Brüning. The Centre was no longer part of the last two governments of the Weimar Republic.

Throughout the political crisis of the early 1930s, the party leadership had no principled objections to forming a coalition with the National Socialists. However, the Centre set conditions for the inviolability of the Constitution and the exclusion of the Nazis from the power structures. Hitler was not satisfied with these conditions, and the black-brown coalition did not materialize. Eventually, the Nazis managed to unite with conservatives, who were less scrupulous, and through this alliance came to power.

In March 1933, the Centre's votes in the Reichstag were decisive for Hitler in his quest to obtain emergency powers to issue laws bypassing parliament. In negotiations with Kaas, the chancellor promised that the institutions of the president, the Reichstag, and the Reichsrat (the upper "land" chamber of parliament) would remain inviolable, and the government would not interfere with the autonomy of the Catholic Church and would facilitate the early conclusion of a concordat with the Vatican. Kaas believed Hitler, and the Centre unanimously voted for emergency powers.

The party self-dissolved in July of the same year. A few weeks later, the Reich concluded a concordat. However, Hitler broke his other promises – he systematically dismantled the Reichsrat and the presidency, completely stripped the Reichstag of political significance, and soon openly restricted religious autonomy, persecuting Catholic public organizations and individual clergy.

Several reasons can be identified for the ultimate failure of the Catholic Centre in the Weimar Republic:

The Centre limited itself to confessional boundaries as a party of Catholics, who made up 30% of the country's population;

The victory of the "right" confessional wing over the "left" working-class wing made the Centre more tolerant of the dismantling of republican institutions;

The priority of "particular" confessional interest over the national interest – the Centre agreed to exchange political subjectivity for the illusion of religious autonomy.

In the "Third Reich," thousands of Catholic priests and laypeople were imprisoned in jails and concentration camps for resisting the totalitarian regime. Some former representatives of the Centre, such as Josef Wirmer and Eugen Bolz, participated in the anti-Hitler plot on July 20, 1944. After the plot failed, they were arrested and executed.

After the collapse of the Nazi regime in 1945, it became evident to most surviving leaders and activists of the Centre that the potential of a purely confessional party was limited. Therefore, former Centre supporters joined forces with former supporters of the Protestant conservative German National People's Party to form the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). Like the Centre, this party included representatives from most social classes – from workers and employees to small business owners and large business owners, but now on a common Christian basis. The CDU's ally in Bavaria became the Christian Social Union (CSU).

In post-war West Germany, the CDU/CSU bloc became the right-centrist pillar of a bipolar party system. The first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1963 was former high-ranking Centre politician Konrad Adenauer, who during the Weimar years was the mayor of Cologne and headed the upper chamber of the Prussian parliament. The CDU/CSU bloc remains one of the leading political forces in the Federal Republic of Germany to this day.

The CDU was also established in East Germany, but under the authoritarian regime that developed there, it was a "system party" and did not influence real decision-making. Nevertheless, after the "Peaceful Revolution" of 1989, East German Christian Democrats won the free parliamentary elections in March 1990, led the government, and ensured the rapid reunification of the GDR with the FRG.

A small part of the Centre's functionaries after the war did not wish to unite with Protestants and re-established the party in its narrowly confessional Catholic form. Its representatives were even elected to the Bundestag and state parliaments, but by the late 1950s, the Centre had completely disappeared from federal and regional politics and has since continued its activities at the municipal level.

Take the test on this topic

History

Center

Did you like the article? Now take the test and check your knowledge about the Catholic Centre Party! Deus Vult!