Article

GERMAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY (DEUTSCHE DEMOKRATISCHE PARTEI)

German liberalism as a political movement emerged after the Napoleonic Wars. Alongside reforming domestic political institutions, German liberals also advocated the ideas of German nationalism and the creation of a unified German state. In fact, the words "nationalist" and "liberal" were synonymous at that time.

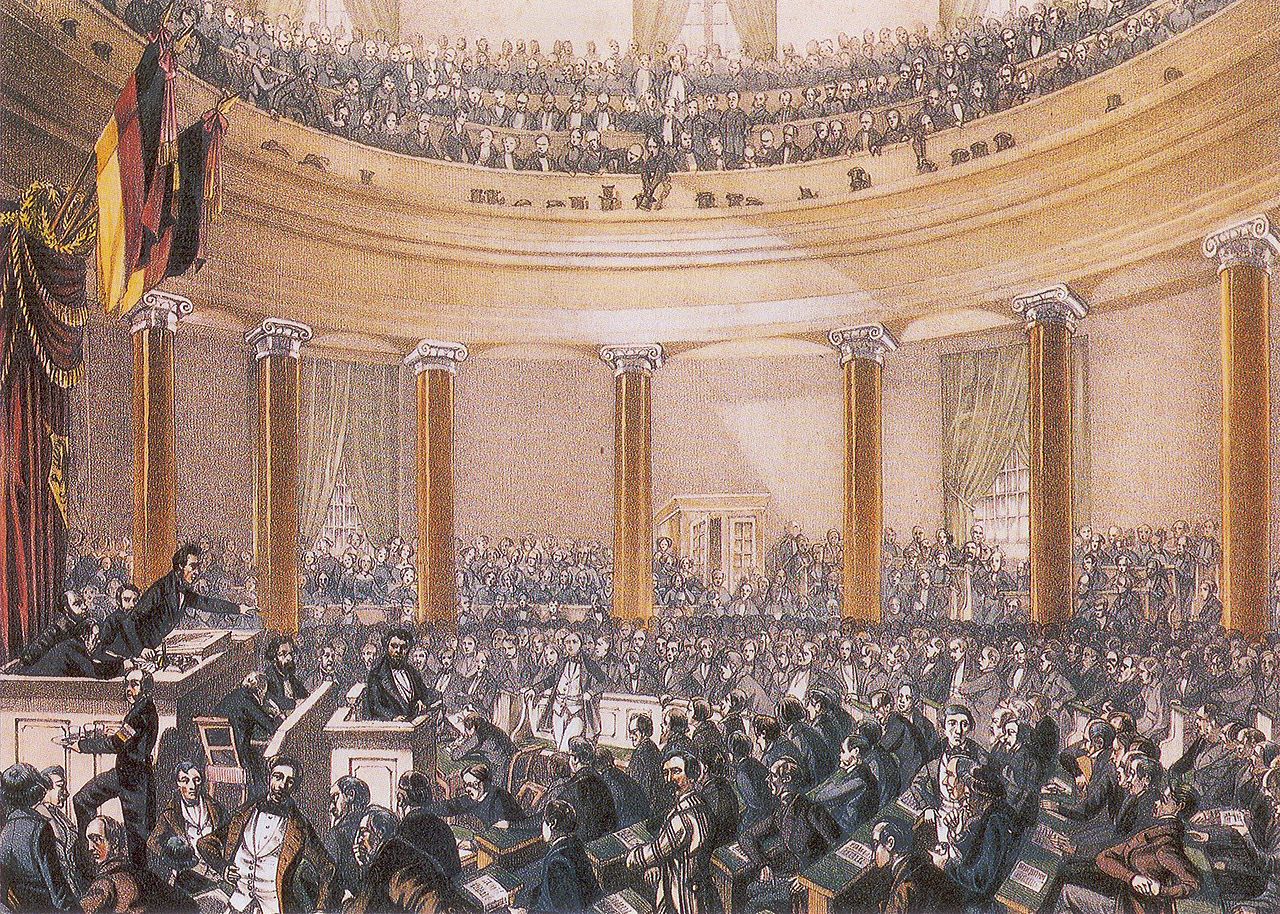

However, the revolution of 1848–1849 during the "Spring of Nations" clearly demonstrated the weakness of the liberal camp in Germany. The liberal all-German Frankfurt Parliament failed to become a real power, and all regional revolutions were suppressed by the armies of German monarchs.

Nevertheless, liberalism did not disappear, and liberals continued to sit in the parliaments of individual German states. However, the failure of the revolution confronted them with a dilemma. If it was not possible to simultaneously create a liberal parliamentary unified German Empire, which of these two tasks should be prioritized—national unity or political liberalization? Different groups of liberals answered this question differently.

To clarify the terminology, it should be noted that the term "left liberalism" in the article, in relation to the first half of the 20th century, refers to the type of liberalism that advocated the expansion of suffrage, was supportive of the introduction of social programs and state regulation of the economy, and considered coalitions with moderate socialist forces possible.

In the Kaiserreich, there were numerous left-liberal parties that approved the creation of a unified German state but simultaneously advocated for further democratization of the political regime. They supported some measures of Otto von Bismarck's government, such as the "Kulturkampf" against Catholics, but rejected others, like the "Anti-Socialist Law," as contradicting the constitutional rights and freedoms of citizens. In 1910, the left liberals united into the Progressive People's Party, which began cooperating with the Social Democrats.

During World War I, progressives held different views on supporting the war's objectives. In 1915, one of the party's leaders, Friedrich Naumann, published the book "Mitteleuropa," which described the economic hegemony of the German Empire over the small states of Central Europe after the Reich's victory. However, by 1917, left liberals, together with Social Democrats and Catholics, called for peace based on mutual agreement. The three parties established close cooperation and began demanding the democratization of the regime. As a concession, in November 1917, Center representative Georg von Hertling headed the Kaiserreich government, and Progressive Party representative Friedrich von Payer became vice-chancellor in the first "parliamentary" cabinet of ministers in German history.

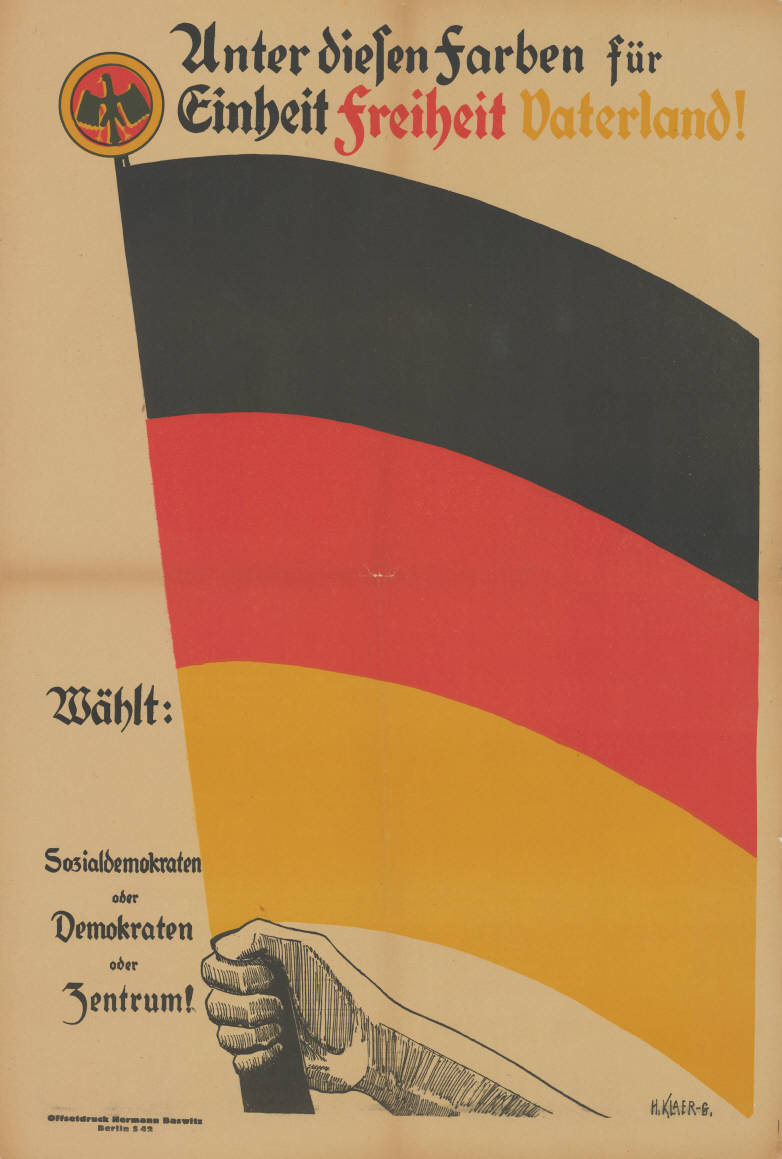

The Progressive Party accepted the November Revolution of 1918 and the overthrow of the monarchy. Immediately after this, the process of reassembling the liberal camp took place. Proposals were made to overcome the historical split and create a unified liberal party, but the perception of the new state system among liberals was so different that unification did not occur. The core of the counter-revolutionary National Liberal Party formed the right-liberal German People's Party (DVP). However, the left wing of the national liberals joined the progressives, and together they founded the left-liberal German Democratic Party (DDP).

In the elections to the Constituent Assembly in January 1919, the DDP consolidated the votes of the majority of the German Protestant "middle class" and achieved its best result in history—18.5%. Together with the Social Democrats (38%) and the Catholic Center (20%), it formed the "Weimar Coalition," named after the Thuringian city of Weimar, where the Constituent Assembly met.

The main author of the Weimar Constitution was the left-liberal lawyer Hugo Preuss. Another prominent DDP member, sociologist Max Weber, served as his consultant. They laid the constitutional foundations of a liberal political order based on the right to private property. However, due to opposition from coalition partners, the liberals could not make Germany more centralized—it remained a federation of autonomous "Free States" within their old "feudal" boundaries. Additionally, Preuss and Weber planted a "time bomb" under the republic's foundation by establishing an extremely strong presidential figure with extensive powers over all other institutions.

In June 1919, the DDP opposed the Treaty of Versailles and even briefly left the "Weimar Coalition" to avoid responsibility for its signing. However, some left-liberal deputies still voted for the ratification of Versailles.

In the June 1920 elections, all parties of the "Weimar Coalition" lost a significant portion of votes and could no longer form a government together without the participation of other parties. The DDP fell from 18.5% to 8% of the votes—most of the disillusioned voters shifted to the right-liberal anti-republicans of the DVP. However, the DDP remained a party at the center of the political spectrum, capable of forming coalitions with both the left and the right, and thus continued to participate in Weimar governments continuously until 1932.

The social base of liberals, both right and left, consisted of employees, officials, academic workers, people of "free professions," merchants, small and large property owners. In the latter case, the left-liberal DDP could particularly rely on industrialists from "new sectors"—electrical engineering, chemical, and mechanical engineering sectors. Their representatives were oriented towards exporting their products and, therefore, interested in the "respectability" of the republican government in the eyes of foreign partners.

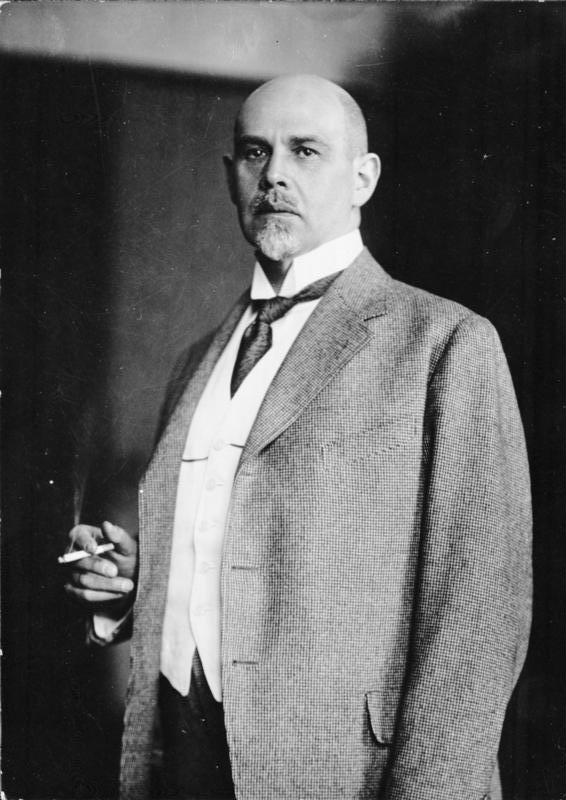

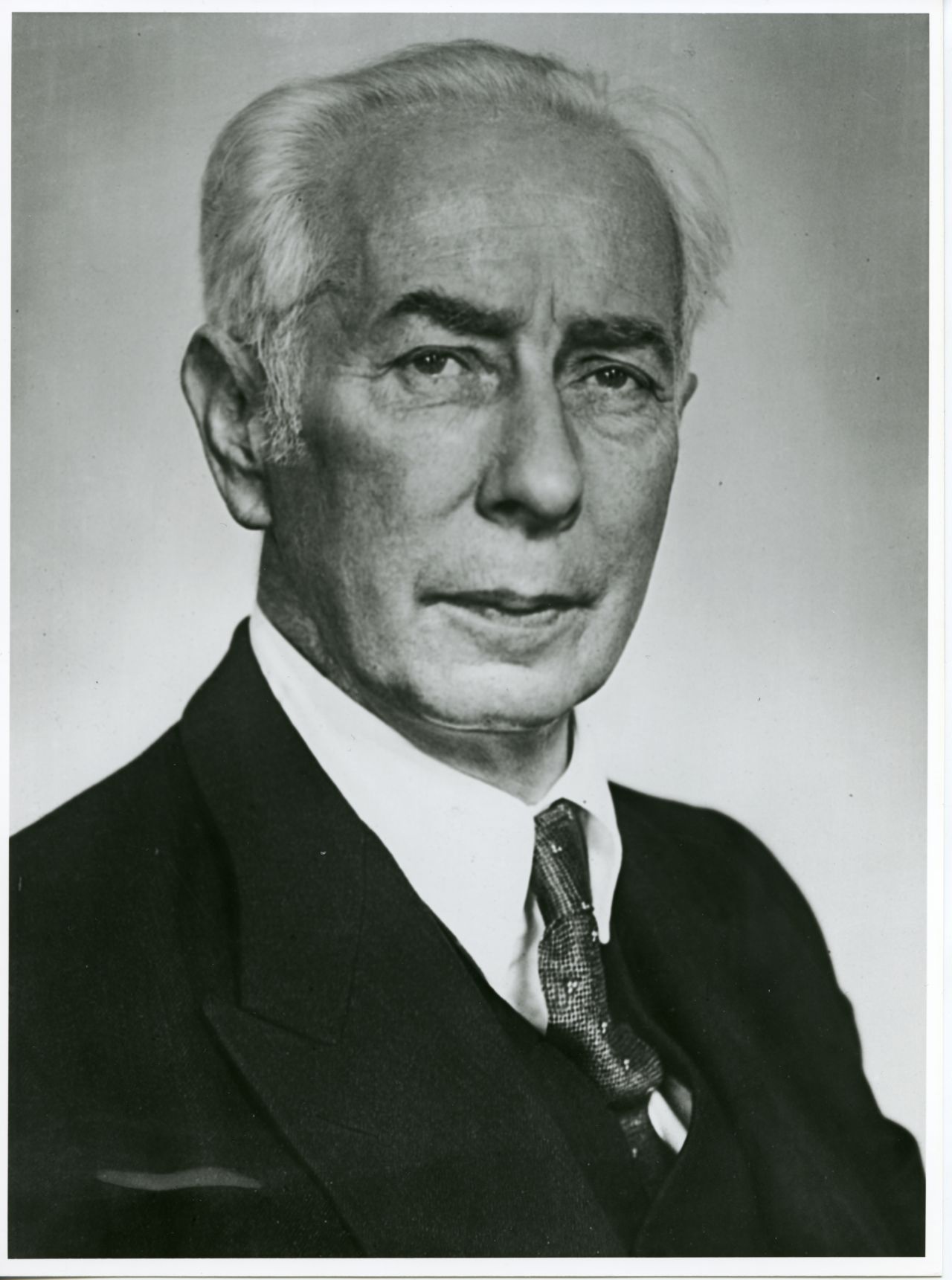

One of the most prominent left-liberal politicians was the owner of the electrical engineering giant "AEG," Walter Rathenau. In the early post-war years, he became the chief negotiator with the Entente on reparations, and in early 1922, he headed the foreign ministry. In this position, Rathenau tried to reduce the amount of reparations and break out of foreign policy isolation. In April, he signed the Treaty of Rapallo with Soviet Russia, which restored diplomatic relations between the two countries and nullified all claims against each other. However, by June, Rathenau was assassinated by right-wing radicals who hated the minister for his Jewish origin and saw him as an agent of foreign powers.

Relying on the "middle layers" of German society, liberals could offer nothing to workers and peasants. Moreover, the unifying German liberalism always advocated for limiting the confessional autonomy of the Catholic Church. Thus, liberals reduced their appeal to Catholics and could mainly count on support only among Protestants.

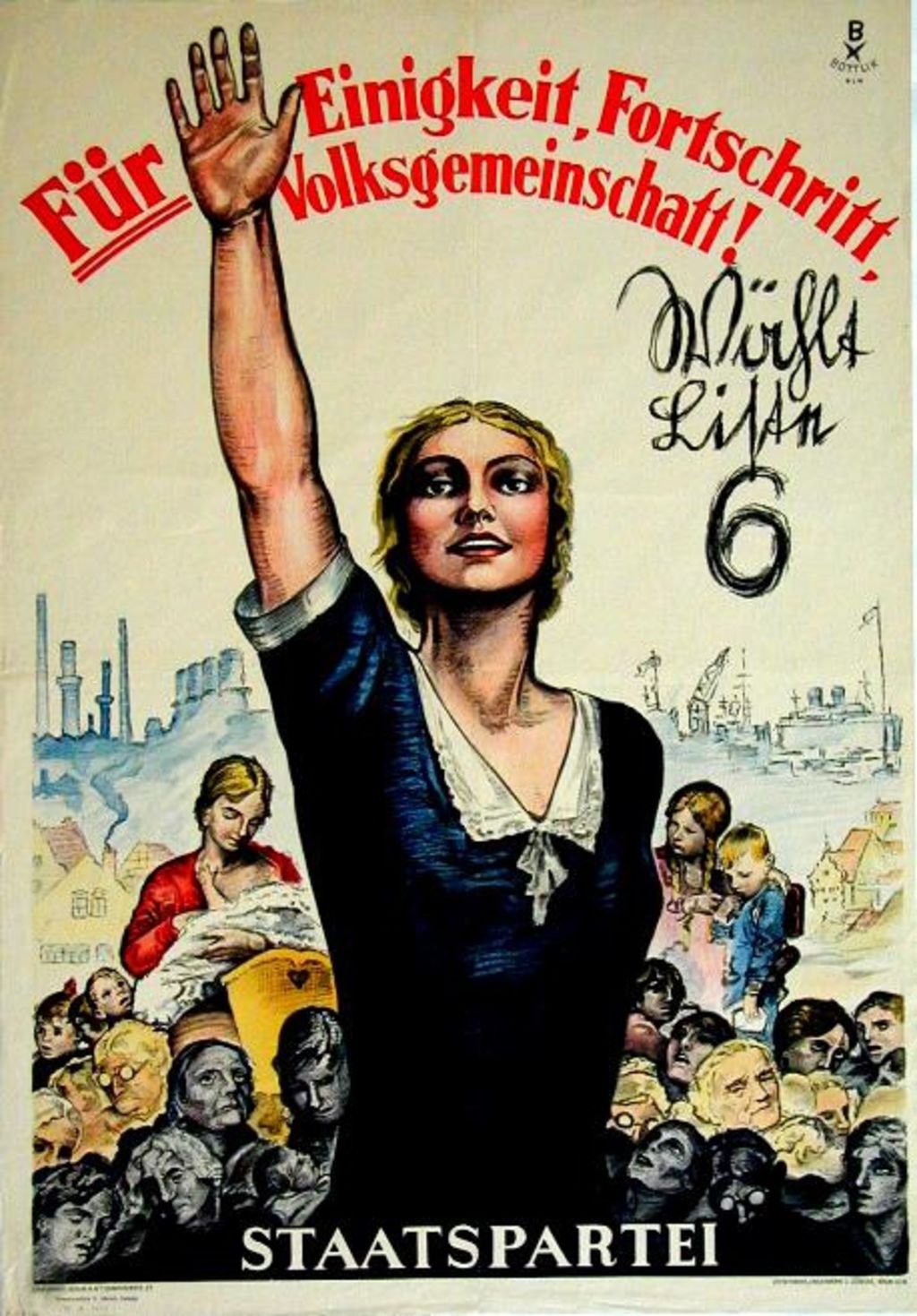

The constant participation of the DDP in all governments made it practically synonymous with the republic itself in the eyes of voters. As the electorate's disappointment in republican institutions grew, the party's popularity declined. In 1930, the DDP leadership, in a desperate attempt to stay afloat, merged with the militarized nationalist and anti-Semitic "Young German Order." The new organization was named the German State Party. This did not help—the nationalist electorate still voted for more radical forces, and principled republicans formed their smaller groups. In the last Weimar elections in 1932 and 1933, the State Party barely garnered 1% of the votes. Its "blood relative" competitor, the DVP, showed similar results. Almost all former liberal voters shifted to the Nazis, who appeared as more active and socially-oriented defenders of the "middle class."

In March 1933, the few left-liberal deputies voted to grant Hitler's government emergency powers to issue laws bypassing the Reichstag. By June, the State Party was forced to dissolve itself.

Reasons for the ultimate failure of left liberals in the Weimar Republic:

The split of the liberal camp into two parties;

A narrow social base limited to the Protestant "middle class";

During the Great Depression, the "middle class" shifted towards radical populists from the NSDAP;

The reputation of a "revolutionary" and "anti-national" party in the eyes of those opposed to the republic and the Treaty of Versailles.

During the Nazi dictatorship, there were limited groups of left-liberal resistance, but they were significantly outnumbered and less significant than similar groups of communists, social democrats, Catholics, and conservatives.

After the defeat of Nazism in 1945, the negative experience of the split in the liberal movement in the Weimar Republic was taken into account and overcome. The right-liberal DVP was discredited by its authoritarian anti-republican position, so it was the left-liberal and democratic DDP that became the foundation for the reassembly of the liberal movement.

In the eastern occupation zone, the Liberal Democratic Party of Germany (LDPD) was created. However, under the authoritarian regime that developed there, the LDPD was a completely "systemic" party and did not influence real decision-making in the GDR.

In the western occupation zones, the Free Democratic Party (FDP) was created. In 1949, its chairman Theodor Heuss, who had been a Reichstag deputy from the DDP during the Weimar years, became the first president of the Federal Republic. The FDP could not compete on equal terms with the larger parties of the Social Democrats and Christian Democrats, but it was precisely its decision on whom to enter into a coalition with that determined the composition of government coalitions.

Currently, the positions of the Free Democrats have significantly weakened, and several times they have not even entered the Bundestag, but the party is still perceived as a significant political force.

Take the test on this topic

History

German Democratic Party

Did you like the article? Now take the test and check your knowledge about the German Democratic Party!