Article

COMMUNIST PARTY OF GERMANY (KOMMUNISTISCHE PARTEI DEUTSCHLANDS)

The origins of the Communist Party of Germany can be traced back to the split of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) during World War I. The majority of socialists at that time supported their own government and voluntarily cooperated with the state system as intermediaries between the Kaiser’s government and the workers.

A smaller group of socialists disagreed with this course. As a result of the split in 1917, the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) was formed, whose members refused to support their own government. The "Independent" Social Democrats welcomed the February and October revolutions in Russia but did not take active steps in Germany itself, waiting for the "objective" historical process to bring the country to revolution.

Within the USPD, a radical group called "Spartacus" formed, led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. The former was the son of one of the SPD's founders, Wilhelm Liebknecht, and was renowned as a principled anti-militarist even before the war. The latter was a prominent figure in the transnational socialist movement. Born in the Russian-controlled Kingdom of Poland, Luxemburg was initially one of the leaders of Polish social democracy, and after moving to Germany, she became a leader there as well. Additionally, Luxemburg established herself as a theorist of Marxist thought. Her work "The Accumulation of Capital" (1913) is considered one of the first conscious attempts to understand global capitalism as an interconnected and unified phenomenon. In her posthumously published pamphlets on the Russian Revolution, Luxemburg criticized Lenin and the Bolsheviks for suppressing civil and political freedoms.

Liebknecht and Luxemburg believed that the "revolutionary situation" in Germany should not be awaited but hastened. For their revolutionary calls, they were arrested, and until October 1918, the leaders of the "Spartacus" group were imprisoned.

In October 1918, the liberalization of the Kaiser’s regime began in Germany to appease the Entente before peace negotiations. As political prisoners, Liebknecht and Luxemburg were released from prison and resumed revolutionary agitation. In early November, a sailors' uprising began in Kiel, after which supporters of the USPD and "Spartacus" led street demonstrations across the country. On November 9, Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed the German Republic, and a few hours later, Karl Liebknecht proclaimed the Soviet Socialist Republic.

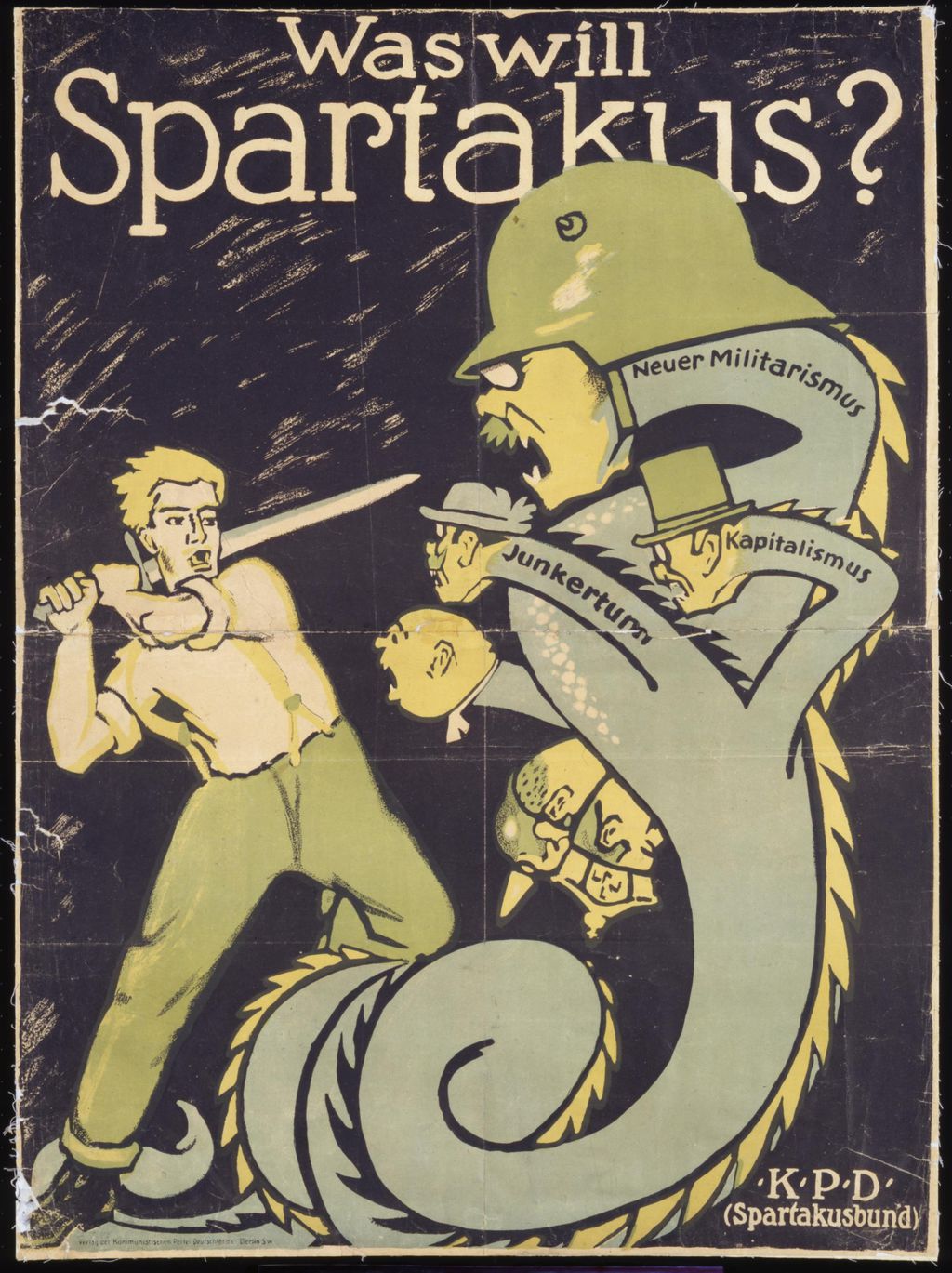

However, the full extent of real power after the revolution passed to the "systemic" SPD, which intended to govern jointly with moderate "bourgeois" parties – the Center and left liberals. Although representatives of the USPD joined the first revolutionary government, they left it by the end of December. On New Year's Eve 1919, Liebknecht and Luxemburg finally separated from the "independent" Social Democrats and founded the Communist Party of Germany (KPD).

In early January 1919, left-radical groups in Berlin, including the USPD and KPD, attempted to overthrow the government of "right-wing" Social Democrats and establish a Soviet republic in Germany. This January uprising was suppressed by volunteer corps (Freikorps), which included a significant number of front-line veterans with ultra-right views. They disliked the Social Democrats, but the "non-systemic left" seemed an even greater threat to them. Liebknecht and Luxemburg were captured and killed without trial. According to an unproven version, the secret order for their extrajudicial execution was given by SPD leaders – head of government Friedrich Ebert and military minister Gustav Noske.

Throughout 1919, communists and other left-radical groups attempted to create Soviet republics across Germany. The most famous examples of this kind were the Bremen and Bavarian Soviet republics. All of them were soon crushed by the Freikorps.

The communists boycotted the elections to the Constituent Assembly and therefore had no representation in this body, which in July voted by a majority for the Weimar Constitution. Germany became "bourgeois-democratic" rather than a Soviet republic.

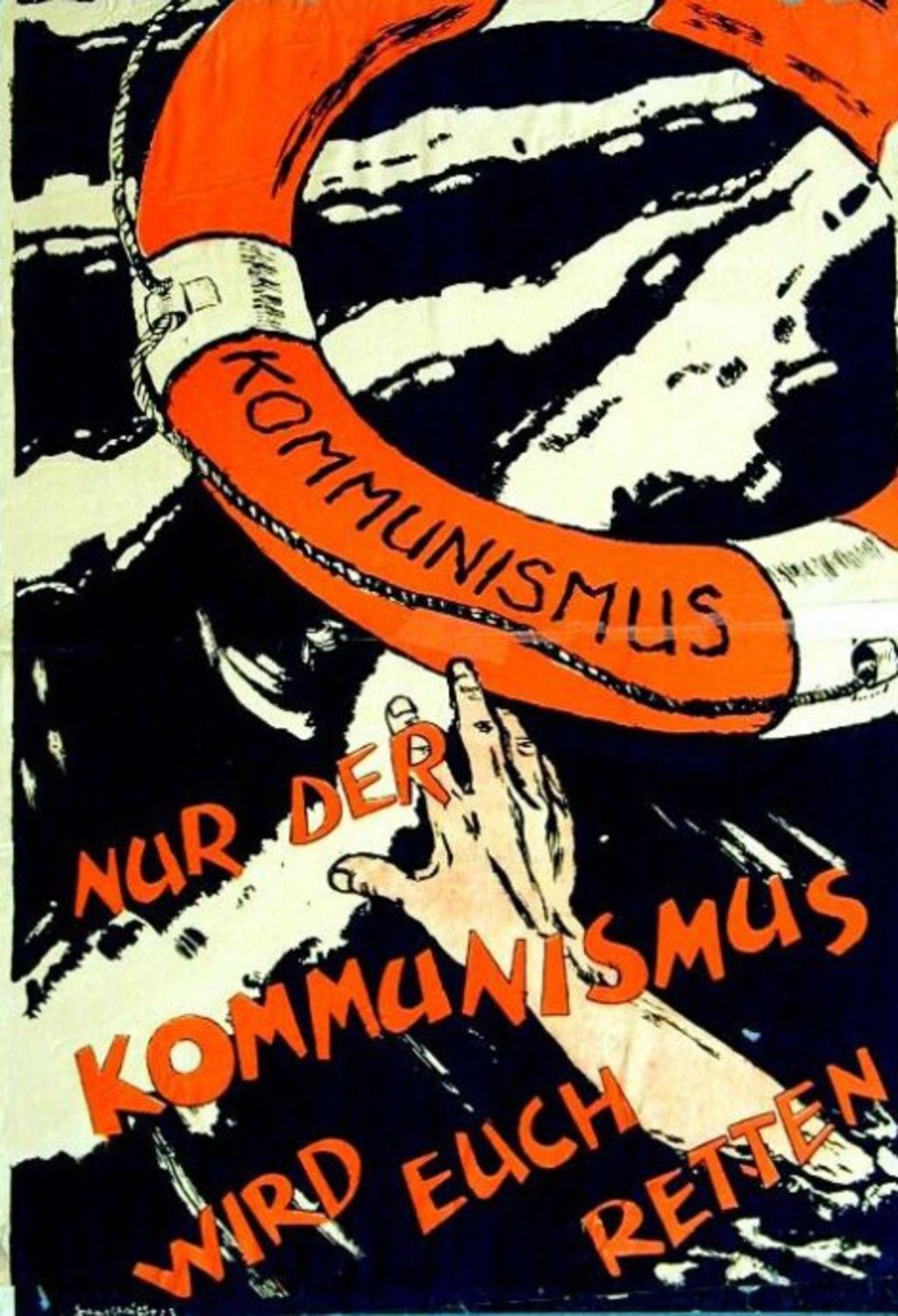

Subsequently, the communists made several attempts to overthrow the newly formed regime. In the wake of resistance to the right-wing Kapp Putsch in March 1920, workers' self-defense units formed the Ruhr Red Army, which temporarily took control of Germany's most industrial region. A year later, in March 1921, a communist uprising occurred in Central Germany. In the fall of 1923, amid hyperinflation, the Comintern seriously prepared for the "German October." At that time, communists joined regional governments in Saxony and Thuringia in coalition with "left" Social Democrats and were ready to turn these states into a base for spreading the communist revolution throughout Germany. An uprising also took place in Hamburg.

However, all these actions were suppressed by the Social Democratic state power with the support of the Freikorps and the Reichswehr. The putschist strategy of the communists did not find support even among the left-wing masses. At the turn of 1920 and 1921, the KPD finally merged with the USPD, but within a few months, a significant part of the "independent" Social Democrats left the party. During this period, the KPD was plagued by constant splits, with each faction having its own vision of party tactics and strategy.

By the mid-1920s, the KPD shifted from organizing futile coups to participating in elections, and this strategy began to bear fruit. If in its first elections in June 1920 the communists received only 2% of the votes, by May 1924 they had 12.5%.

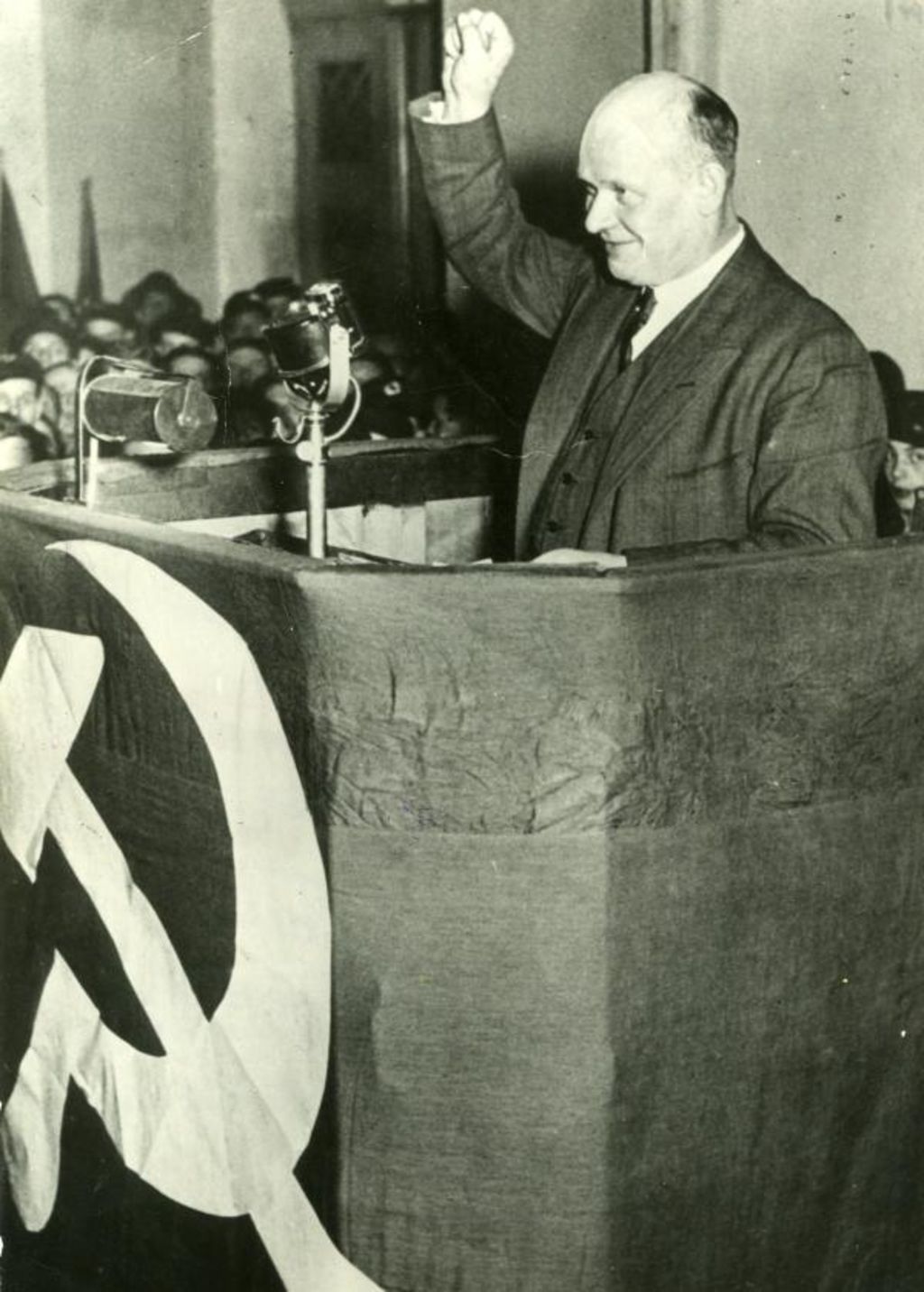

In the spring of 1925, the organizer of the Hamburg uprising and the new party leader Ernst Thälmann was nominated as a candidate for the country's presidency. In the first round, he received 7% of the votes and came in fourth place. In the second round, the battle was to be between the consolidated right-wing candidate – Kaiser’s Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, and the consolidated republican candidate – Chairman of the Catholic Center Party Wilhelm Marx. The communists refused to support the "bourgeois" Marx and did not withdraw Thälmann in the second round. He received 6.5% of the votes, while monarchist Hindenburg surpassed republican Marx by 3% – with 48% against 45%. The Social Democrats then declared that Hindenburg became president "by the grace of Thälmann."

In 1928, Thälmann, who began to orient himself towards Stalin as his Moscow patron, managed to finally defeat all "opposition" factions within the Communist Party. The expelled communists formed their small Trotskyist or Bukharinist groups, but they had no serious influence.

During the Great Depression, the KPD became the main electoral beneficiary of the crisis alongside the National Socialists. The communists' results consistently grew: 10.5% in 1928, 13% in 1930, 14.5% in July 1932, and 17% in November 1932. The KPD became the third most popular party in the country after the Nazis and Social Democrats. In Berlin and the Ruhr area, it was the most popular party.

In the 1932 presidential elections, the KPD again nominated Thälmann. In the first round, he received 13% of the votes, while Hitler got 30%, and the incumbent president Hindenburg got 49.5%. In the second round, Thälmann received 10%, compared to 37% for Hitler and 53% for Hindenburg.

Besides revolutionary rhetoric, the Communist Party actively flirted with nationalism. The KPD demanded a revision of the Treaty of Versailles as unjust to Germany and the right for Germans to reunite with all their compatriots in a single socialist state.

Paramilitary communist organizations were very active. In the first half of the 1920s, these were the "Proletarian Hundreds," then the "Alliance of Red Front Fighters" ("Rotfront"), and after its legal ban in 1929 – the anti-fascist "Kampfbund." Communist militants regularly engaged in street clashes with Nazi stormtroopers, the right-conservative "Steel Helmet," and the Social Democratic "Reichsbanner."

According to Comintern instructions, in the early 1930s, the KPD leadership considered the party leadership of the SPD, not the National Socialists, as the main opponent of the labor movement. Fascism and the capitalism that spawned it were "objectively" supposed to suffer inevitable historical defeat by the working class soon, but the Social Democrats, labeled "social fascists," were misleading the broad working masses and delaying the moment of their final victory. The KPD called for a "united anti-fascist front" of the entire labor movement, but this front implied the overthrow of the Social Democratic party leadership and the further following of the Social Democratic masses to communist instructions. In turn, the Social Democrats saw the communists as "red fascists" – enemies of the Weimar Republic, just like the Nazis, and therefore also refused to ally with the two Marxist parties.

In fairness, it should be noted that uniting efforts did not automatically mean the defeat of the Hitler movement. Indeed, if you add up the votes for the Social Democrats and communists in the Reichstag elections in November 1932, their 37.5% is more than the Nazis' 33%. However, the question of power was no longer decided in the Reichstag but in the reception room of the conservative President Hindenburg. The number of parliamentary seats had no practical significance. Moreover, a united Marxist front would likely have consolidated the "bourgeois" flank, which made up the remaining 60% of the electorate. Then it would have been even easier for the Nazis, who positioned themselves as defenders against the "red threat," to gain power.

Immediately after Hitler was appointed chancellor in January 1933, state repression against communists began. On the night of February 28, Dutch communist from a marginal left-radical group Marinus van der Lubbe set fire to the Reichstag building, giving Hitler a pretext to transition to full-scale legalized terror against all political enemies. Communists were considered the main target, and the KPD was effectively banned.

The communists did not offer any organized resistance. The main reason should be considered their belief in the "objectivity" of the historical process, according to which the Nazis were supposed to fall within a few months, and therefore the Communist Party should not risk its cadres in an uprising.

Despite intimidation and pressure in the last semi-free Reichstag elections in March 1933, the Communist Party still received more than 12% of the votes. However, the communists' parliamentary mandates were immediately annulled. During this period, many party officials were captured, imprisoned, sent to concentration camps, or even killed. Among those arrested was the party leader Thälmann. Some party activists managed to emigrate, while others went underground and continued the struggle.

Reasons for the ultimate failure of the communists in the Weimar Republic:

The KPD limited itself to "class" boundaries as a workers' party;

Orientation towards the working class led to a priority struggle against the Social Democrats, who fought for the same electorate, rather than against the Nazis;

The reputation of "revolutionaries" repelled the vast majority of the population;

Organizational and ideological dependence on the Comintern and the Politburo in Moscow;

Belief in the "objectivity" of historical processes led to an underestimation of the Nazi threat.

During the Nazi regime, many illegal communist groups continued to conduct underground struggle, engaging in agitation and sabotage. The party leadership in exile, following Comintern instructions, recognized the thesis of "social fascism" as erroneous and began calling for the consolidation of all anti-fascist democratic forces within "Popular Fronts."

Some KPD leaders were eliminated in the USSR during the "Great Terror." In Germany itself, communist underground fighters were also regularly exposed, arrested, and executed. Ernst Thälmann was executed without trial in the Buchenwald concentration camp in August 1944.

After the defeat of Nazism in 1945, the negative experience of the split in the socialist movement was taken into account in the Soviet occupation zone. In 1946, local Social Democrats and communists united to form the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), which was the ruling party of the GDR until 1990. Former KPD members – Wilhelm Pieck, Walter Ulbricht, Erich Honecker, and many others – formed the ruling elite of the new state.

The Social Democrats in West Germany refused to unite with the communists. In the first Bundestag elections in 1949, the KPD gained almost 6%. However, in the next elections in 1953, it failed to overcome the five-percent barrier and did not enter the West German parliament. By 1956, the Federal Constitutional Court banned the Communist Party as extremist. Communists had to continue their activities as part of smaller and more isolated groups.

In 2007, the historical successors of communist organizations from West and East Germany united in the "Left" party, which remains the main proponent of leftist ideas in German politics.

Take the test on this topic

History

Communist Party of Germany

Did you like the article? Now take the test and check your knowledge about German communists!