Volunteer and Revolutionary: An Attempt to Save the Russian Army in 1917

In 1917, the Russian army found itself in a deep crisis. In the context of the ongoing war, unconventional methods were needed to revive the military spirit. Thus, the concept of a volunteer revolutionary army emerged, which was intended to inspire the mobilized and eventually replace them with volunteers. To find out how this experiment ended, read the article by historian Konstantin Tarasov.

10.07.2025

Konstantin Tarasov

Historian

After the February Revolution of 1917, the Russian army found itself in a deep crisis. Low morale, mass desertion, tense relations between the rank and file and the command staff, and a lack of supplies all led to catastrophic consequences for the front. After the fall of the monarchy, the Provisional Government did not intend to end the war, and it faced a serious question: how to revive the armed forces, which were showing weak signs of life?

A great many initiatives emerged. The most successful should be recognized as the project to replicate the successes of Lazare Carnot from the era of the French Revolution at the end of the 18th century. At a critical moment for France, this military engineer and member of the Convention proposed the reorganization of the armed forces to increase their combat capability. One of the measures was the merging of the best elements of the old army with volunteers from the rear. The successful implementation of the reform created a victorious revolutionary force, for which Carnot was awarded the honorary title of "Organizer of Victory."

During the Russian Revolution, followers of Carnot's ideas managed to obtain permission to implement their plans from the high military command. From mid-May 1917, with the approval of Supreme Commander-in-Chief General Alexei Brusilov, shock units began to be formed from front-line parts, and volunteer units were created in the rear.

The shock units at the front consisted of patriotically minded soldiers and officers who swore an oath to die for the Motherland. The shock troops were to have more privileges, better equipment and armament, and their pay was also better compared to the rest of the army. However, discipline was strictly enforced among them. Throughout 1917, the states of the shock formations were repeatedly clarified towards strengthening.

One of the first such units at the front was the Kornilov Shock Detachment, later a regiment, created in May as part of the 8th Army, which at that time was commanded by General Lavr Kornilov. By the end of August, there were already 290 such units. These units differed in their purpose from the German stormtroopers and Italian Arditi, which emerged as a reaction to the stalemate in the war. The shock units were not intended for covert attacks on weak points of the enemy to prepare a breakthrough by the main forces, but were meant to inspire other front-line soldiers by their example.

The same patriotic content lay at the foundation of the "Death Units," formed from volunteers in the rear. Initially, it was assumed that they would be recruited mainly from military schools and among sailors of the Black Sea Fleet who were not involved in combat operations. However, in the end, all citizens of Russia who were not subject to conscription or were subject but not yet called up to the army could enlist as volunteers: youth, students, intellectuals, workers. In this way, they were supposed to show that the whole country had united for victory over the enemy.

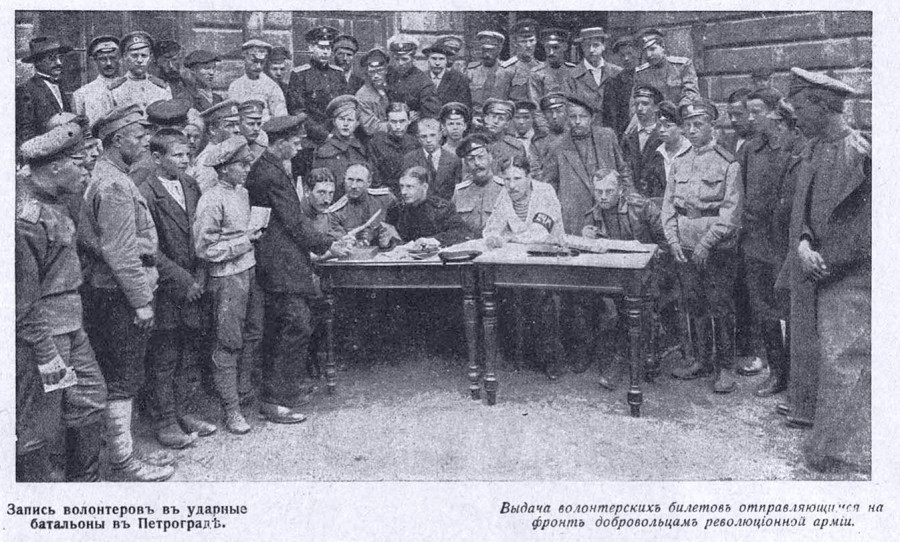

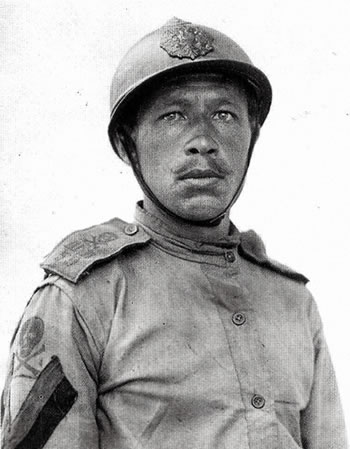

The volunteer movement turned out to be massive. The Death Battalions were created by soldiers who had escaped from captivity, disabled warriors, holders of the St. George's Cross, and others. The most famous of them was the Women's Death Battalion under the command of Maria Bochkareva. The All-Russian Central Executive Committee for the formation of revolutionary battalions from rear volunteers formed about 80 battalion committees, through which approximately 40,000 people joined the active army from June to July. From them, two regiments and over 50 battalions were subsequently created.

The baptism of fire for the new units was the offensive of the Southwestern Front, which began on June 18. In the first two days, Russian troops achieved tactical success, capturing up to three lines of enemy trenches. The main force of the offensive was precisely the shock units, which continued to move forward, trying to draw the main forces along with them. But soon the advance slowed. Infantry regiments either followed the shock troops without much enthusiasm or completely went out of control, refusing to advance. Often, remaining under direct fire and without any support, the shock units suffered heavy losses. By early July, the offensive had turned into a complete failure, and Russian troops were forced to retreat, losing combat order.

The command's hopes that the shock troops would have a positive moral impact on the rest of the army were not fulfilled. As one of the initiators of the creation of volunteer units, Lieutenant Colonel Viktor Manakin, reported to the Minister of War: "The shock battalions did not provide any particular benefit in terms of psychological impact on neighboring units, causing instead resentment towards themselves from units refusing to serve or retreating in disorder.".

The command increasingly saw in the volunteers a force for moral influence on the units that had gone out of control and for imposing order in the rear. Despite the defeat, the combat capability of the volunteer formations was rated very highly, especially against the backdrop of the worsening disintegration of the rest of the army and the growth of anti-war sentiments.

The failure of the offensive forced the military command to sit down again to plan the military campaign for the next year. In the fall, proposals for a simultaneous radical reduction of the army and active infusion of volunteer units to the front line were increasingly heard in the headquarters. Activists of this movement, dreaming of a Volunteer Revolutionary Army as a striking force for the offensive, began to propose projects for the complete "voluntarization" of the armed forces. They believed that the 15-million-strong wartime army could easily be replaced by 3 million motivated volunteers. It was assumed that due to higher morale, they would be able to conduct military operations much more successfully.

The military ministry, headed by Alexander Verkhovsky in September, and the Supreme Command Headquarters, where Chief of Staff Nikolai Dukhonin and his closest assistant Mikhail Diterikhs played key roles, took up the matter. The Minister of War believed that first of all, it was necessary to radically reduce the size of the army by getting rid of all "unfit elements." The shock units, which had proven to be a successful means of combating demoralized regiments, were hoped to restore discipline in the rear and form a militia from selected officers and rank-and-file personnel.

By October, Dukhonin and Diterikhs presented the "Program of Measures to Raise the Combat Capability of the Army by Spring 1918." It implied the reduction of the army, reorganization of the armed forces, and cleansing of "disloyal persons" among the officer corps and rank-and-file. The front was to be freed from "old men" and youth, who were considered most susceptible to demoralizing propaganda. According to the calculations of the Headquarters, by May 1, 1918, the size of the army could be reduced to 7.5 million people, of which only 4 million would make up the combat composition of the front-line units.

On the assignment of the Provisional Government, the Headquarters also developed a project for a volunteer Russian People's Army. The strongest element was selected from the front-line parts, and on its basis, regiments, divisions, and corps were deployed as the foundation for the new army. Its core was to be the parts of the St. George and shock battalions, training commands, military formations from solid parts, Cossacks, etc. The remaining military units were planned to be reduced to work companies with particularly strict discipline, thus breaking them into small, controllable units. According to the plan, the new army was to be replenished by compatriots, natives of one district. It was believed that the territorial principle of formation would give the new units greater cohesion.

Undoubtedly, the measures proposed by the Headquarters were based on the experience of creating shock battalions. But somewhere on the horizon loomed the shadow of Lazare Carnot. The new army was to be small but capable and with high salaries for servicemen. The authors of the project believed that if the army did not undertake large-scale offensive operations, the proposed measures would be sufficient for defense until the end of the war.

For some senior officers, this program was unthinkable. They held their heads, not knowing how such small forces would hold extended sections of the front. Others were ready to take any measures that gave at least the slightest chance to hold the defense, not to mention active actions. Right before the fall of the Provisional Government, measures were approved for the partial reduction of the army, preparatory work for demobilization, replenishment of active units, the adoption of the national principle of replenishment, volunteering, and planned improvement of the material support of personnel.

The command urgently began to implement these measures, which were allotted no more than six months. Partial demobilization began on October 10. The oldest soldiers of the 1897–1898 draft, that is, 41 years and older, were sent home. Partial demobilization continued even after the Bolsheviks came to power. After October, in November – December, the next in line, the 1899–1901 drafts, were demobilized. On November 23, the People's Commissariat for Military Affairs announced its intention to reduce the army "by demobilizing soldiers of older ages and calling up soldiers up to 20 years old." In other words, the course for gradual demobilization fully corresponded to the interests of the Bolsheviks.

However, there were different opinions on the creation of a volunteer army. The Bolsheviks' program, like that of other socialists, implied the creation of a people's militia, that is, a transition to the general arming of the people and the elimination of the professional army as such. However, life made its adjustments. The peace negotiations in Brest-Litovsk by mid-December had obviously reached an impasse. It became clear that the resumption of hostilities against Germany was a realistic scenario in the near future. At the same time, in the Russian trenches, such a prospect did not cause a storm of revolutionary enthusiasm. Reports from the front left the Bolshevik leadership in no doubt that the army was in a deep crisis, and it was impossible to continue fighting with its current composition. Therefore, it was necessary to prepare not for complete demobilization, but for the creation of new armed forces capable of conducting military operations.

On December 17, members of the People's Commissariat for Military Affairs, representatives of the General Staff, and delegates of the demobilization commission discussed the situation at a special meeting. It was the general staff officers who insisted that restoring the combat capability of the existing army was impossible and that a transition to a small volunteer army with the strictest military discipline was necessary. The meeting participants concluded that given the already announced demobilization, only volunteers could be left in military service. If their number was insufficient, the contingent had to be supplemented with soldiers of younger ages.

The next day, Supreme Commander-in-Chief Nikolai Krylenko spoke at a meeting of the Council of People's Commissars. The leadership of Soviet Russia agreed on the need to take "enhanced measures to reorganize the army while reducing its composition and strengthening its defense capability." In other words, the idea of general arming of the people and complete demobilization was postponed to a distant future. The urgent task again became the reorganization of the army to protect the country from the German offensive.

The new authorities, however, could not rely on the former shock battalions. The events of October showed that the volunteers were open opponents of the Council of People's Commissars. They refused to recognize the change of power and participated in street battles against the Bolsheviks in Petrograd, Moscow, and Kiev. One of the first and most bloody battles of the Civil War took place at the end of November near Belgorod. There, in battles that lasted twelve days, shock troops breaking through to the Don clashed with Soviet troops, with several thousand people on both sides. The detachment of shock units was scattered, and its remnants disbanded, after which the volunteers individually reached the territory not controlled by the Council of People's Commissars. On December 9, Supreme Commander-in-Chief Nikolai Krylenko drew a line under the shock movement by publishing an order to liquidate such units in the rear and at the front.

The only source of volunteers trusted by the Bolsheviks became the Red Guard detachments and elements of the old army that were ready to defend Soviet power. On December 22, at a meeting of the People's Commissariat for Military Affairs with representatives of the General Staff, attended by Lenin, it was decided to send Red Guard detachments from the Petrograd and Moscow military districts to the front as soon as possible and to begin forming new ones.

In the end, just before the New Year, the General Staff presented a plan for the reorganization of the army, prepared at the direction of the People's Commissariat for Military Affairs. This project implied reducing the existing infantry divisions at the front from 159 to 100, withdrawing unnecessary military units to the rear, and forming a new army from volunteer soldiers consisting of 36 divisions of 10,000 people each.

Krylenko publicly announced these plans on December 29. The address of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief spoke of the creation of a Revolutionary People's Socialist Guard at the front, into which volunteers from the front and rear (workers and soldiers of rear garrisons) were to be incorporated. "Those who cannot, who do not feel the strength to go into this struggle, let them not go. We need a revolutionary army of fighters, not an army of those who think only of their own hut," – Krylenko urged.

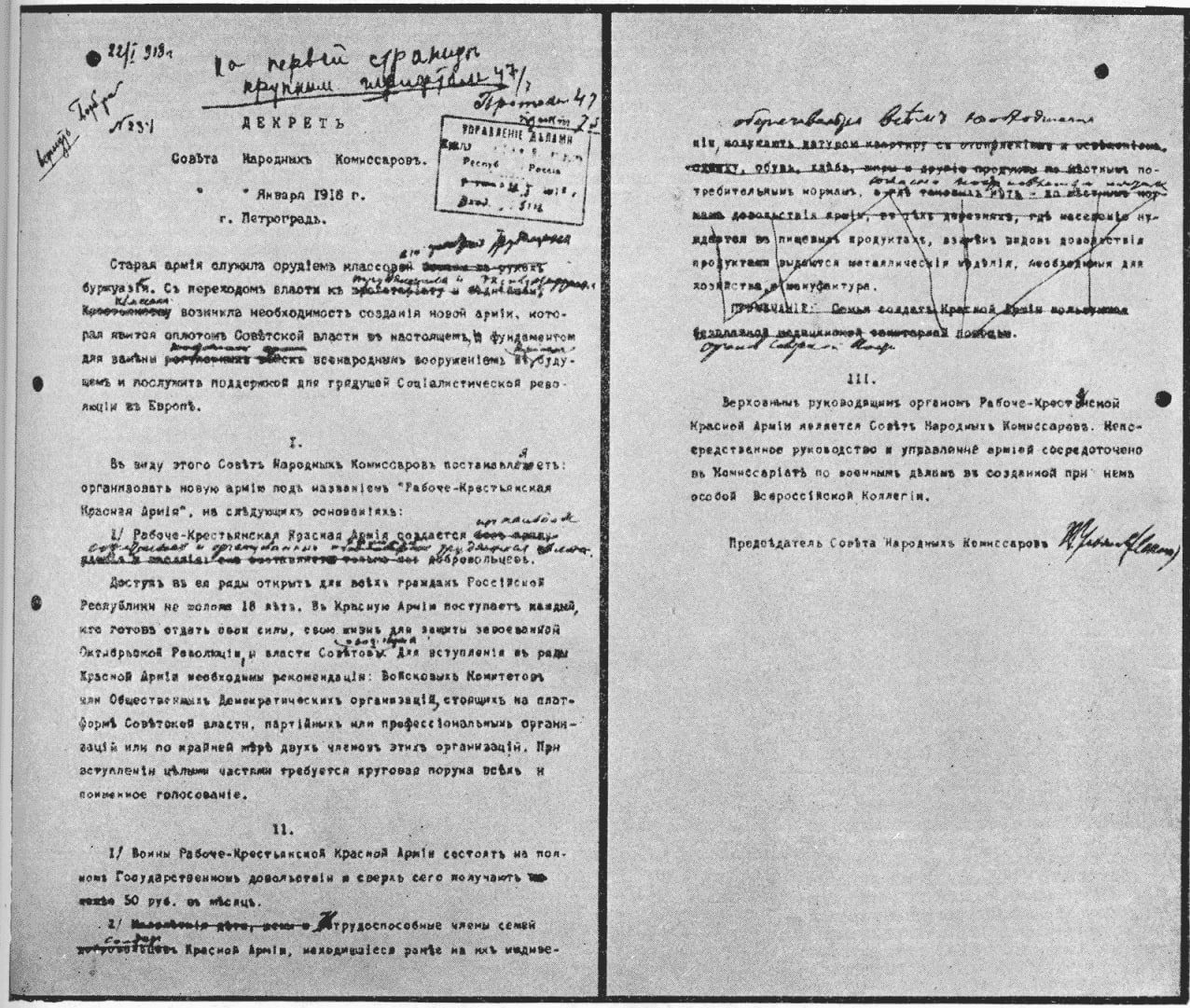

On January 15, 1918, Lenin signed a decree on the creation of the Workers' and Peasants' Red Army. As can be seen from the draft document, the head of the Soviet government erased all references to the volunteer method of staffing the new army. Nevertheless, the Bolsheviks and their allies considered it necessary to follow Marxist principles, rather than being guided by the ideas of Lazare Carnot. But still, in practice, it was precisely about the "voluntarization" of the old army.

At the front, the campaign to enlist volunteers in the new armed forces, organized by Bolshevized soldiers' committees and revolutionary committees, did not yield significant results. The deployment of volunteer recruitment fell on the last decade of January. It could not reach any significant size. Thus, according to the calculations of researcher Pavel Golub, the front provided only 70,000 volunteers by spring, which was approximately equal to only one percent of the entire army's strength.

On February 18, 1918, just two and a half weeks after the publication of the decree on the creation of the Red Army, Austro-German troops launched an offensive. It was necessary to deploy volunteer detachments to the front line in a situation of a collapsing front. Only by March was it possible to concentrate a sufficient number of units on the Petrograd direction near Pskov and Narva to slow down the enemy's advance on the capital.

On March 3, 1918, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed, which nevertheless did not protect against further offensives by the Central Powers. In the months following the conclusion of peace, German operations continued in the Caucasus and Finland, as well as in the southern direction. The enemy occupied Odessa, Yekaterinoslav, Kharkov, Belgorod, Rostov-on-Don, and the Taurida Governorate.

Serious failures in creating a volunteer army, as well as the beginning of the Civil War and intervention, forced the Soviet authorities to reconsider their plans again. The new People's Commissar for Military Affairs, Leon Trotsky, sought to abandon "partisanship," as poorly managed red volunteer detachments were then called. On May 29, after lengthy discussions in the Bolshevik leadership, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee adopted the "Resolution on the Compulsory Recruitment into the Workers' and Peasants' Army." It emphasized that the transition to general mobilization of workers and the poorest peasants was necessary "both for the struggle for bread and for repelling the impudent counter-revolution, both internal and external, arising from hunger.".

The same path of abandoning voluntarism in favor of mobilizations was followed by the opponents of the "reds." The People's Army, created in June by the anti-Bolshevik Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly, was also initially built on a voluntary basis. However, the size of the first volunteer units was negligible compared to the forces of the red troops threatening Samara. By the end of the month, the leadership of the People's Army was forced to resort to mobilization, which, however, showed that the peasants did not want to fight in the Civil War. Even the White Army, which during its formation on the Don was called the Volunteer Army, was forced to abandon staffing exclusively with volunteers. Already in August, the white command, following the "reds," began to resort to mobilizations in the territories under their control. However, those mobilized on both sides responded to this with mass desertion.

Inspired by the idea of voluntarism, the opposing sides of the Civil War began with appeals inviting all who wished to fight for their ideas. However, dreams of attracting highly motivated fighters were shattered by the reality where numerical superiority and a good material base were of much greater importance.

Although Lazare Carnot was involved in drafting the decree on the first mass conscription in history, during the Civil War in Russia, the French military engineer was rarely remembered. The realities of the internal conflict required more stringent and massive methods of mobilization than those that could be relied upon by relying solely on volunteers. In the era of mass armies, the idea of voluntarism proved to be of little use for both defense against an external enemy and for internal conflict.